How to start researching your family’s genealogy

(MIRROR INDY) — These days, the phrase “unprecedented times” is tossed around again and again. But in reality, our ancestors have gone through similar events and crises.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Nichelle M. Hayes, a local genealogy expert, thought about what her mother, grandmother and great-grandmother endured in their lifetimes.

“They were able to come out on the other side,” Hayes said. “I am them, and they are me. They poured into me. So if they can survive those things, then I’ll be able to survive this.”

That’s why she recommends documenting your experiences with current events – like she did during COVID.

“Because 50 or 100 years from now, my descendants might be thinking, ‘So what did they do? How did they deal with it?’”

Mirror Indy interviewed Hayes, a former president of the Indiana African American Genealogy Group, and Nicole Martinez-LeGrand, Indiana Historical Society’s curator for multicultural collections, to get their advice on how to start researching your family — a process that can help you understand yourself better.

Nichelle M. Hayes: Start with a ‘brain dump’

While digging into her family history over the decades, Nichelle M. Hayes has found some intriguing things.

Looking into her dad’s, she hit a wall. At some point, there was a split: Some of her relatives kept the name Hayes, and others were Williams. But why?

Eventually, she found out that her great grandfather, Hubert Hayes, was forced to change his name when he moved to Indianapolis and got a job. His employers wouldn’t let him keep his mother’s last name. Two cousins showed up to verify he was who he said he was, and he got a delayed birth certificate. From then on, his part of the family became the Williams.

Hayes, who owns Hayes Consulting, writes about discoveries like these on her blog called “The Ties That Bind.”

“I love genealogy. It’s a passion,” said Hayes, who was the founding director of the Center for Black Literature & Culture at Central Library. “And I love to bring people together. And beyond the facts and figures, it’s about connecting the family.”

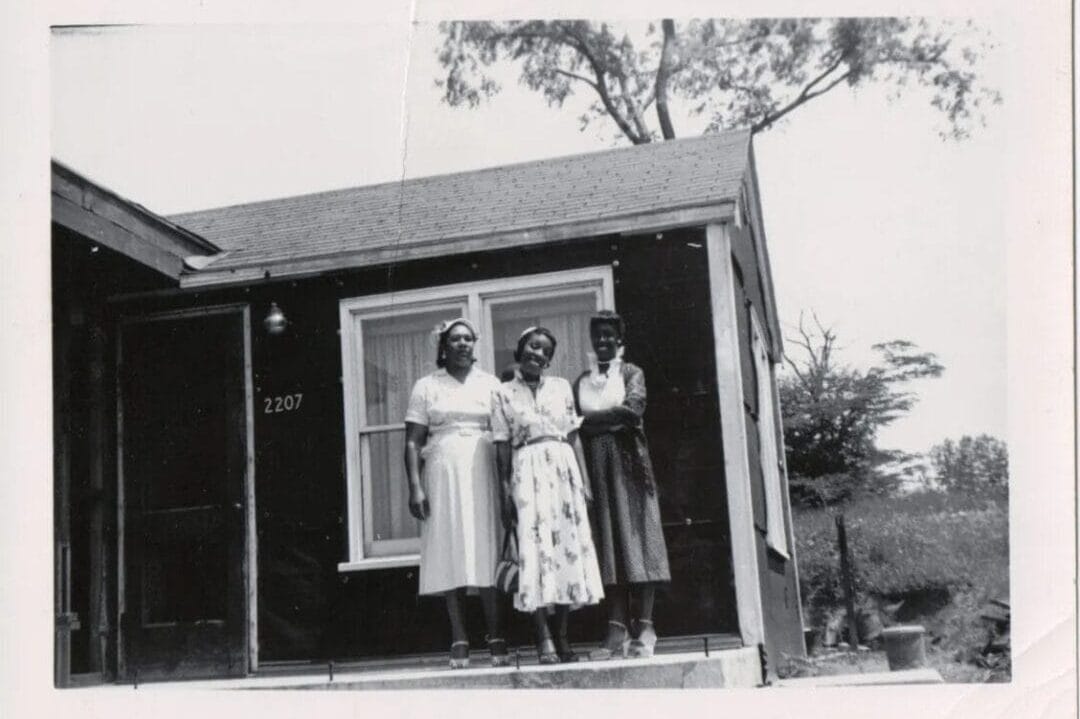

As she researches the past, she’s creating a record of her family for the future. Hayes interviews her family at holidays and reunions. Last week, she put together LEGO sets with her great-nieces while visiting her brother, and she made sure to take a photo.

“I’m gonna put those in the albums so that people can see ‘this is what they looked like when they were younger,” Hayes said.

How to research your family’s history and genealogy:

- Start with a “brain dump” of names of family members. List yourself first, then family members as far back as you can. Starting with an ancestor that’s further away and working back toward yourself could be confusing.

Focus on one line (name or family unit) at a time. Trying to research multiple groups of people will get confusing.

- Some Black families can run into the “1870 barrier.” That’s the first year that formerly enslaved people were shown in the census. Look for other documents like probate records and wills.

Hayes’ ancestors were from St. Mary Parish, Louisiana, so she visited the Curtis family farm to understand what it was like to live in the area and the work it took to buy the land. She suggests visiting where your family is from and recommends reading, “Finding a Place Called Home: A Guide to African-American Genealogy and Historical Identity,” by Dee Parmer Woodtor.

- Keep notes – whether in a journal or online – to document what you are finding and where you got it from.

- Interview your family members often, and don’t correct them or interrupt. Listening and taking notes will often encourage them to open up more. Record audio and video when you interview family members. Take advantage of holidays or family reunions to ask questions.

When she interviews her family, she starts with asking for memories from younger days, including: Who did you grow up with? Where did you grow up? Were you raised by your parents or other family members? How far back can you name relatives?

- Digitize everything – and save photos in a PNG format, not JPEG. This will keep them at a higher resolution.

- Make sure to give someone else access to your digital archive so it isn’t lost to history when you die.

Nicole Martinez-LeGrand: Preserve those photos

Nicole Martinez-LeGrand didn’t always think of herself as a “public history person” – an academic who reads and writes about history.

Since seventh grade, she has dreamed of working at museums. While in graduate school in the early 2010s for her museum studies degree, she asked her husband for a 23andMe DNA testing kit as a birthday present. It was the start of her journey researching her family’s genealogy.

After jobs at Newfields and the Children’s Museum, she became the Indiana Historical Society’s curator for multicultural collections in 2016. There, she helps families research their genealogy and compiles oral histories of Indiana’s Asian and Latino populations.

When her grandfather, Antonio Martinez, died in 2017, she and her twin sister started seriously researching their family.

“We didn’t know too much about him,” she said. “He had moved back to Mexico when we were toddlers, and then he would come back for baseball season.”

They also knew their grandmother was much younger than Antonio. How did they meet? Who were his siblings? Was he the oldest child?

There was much more to discover, and her job working with Latino families at the historical society had prepared her to research her family’s history in Mexico and the U.S.

Now, she knows Antonio Martinez ran the panadería, or bakery, in his hometown in Mexico. It wasn’t paying enough for him to maintain a family, so he left for the U.S. in his 30s. Eventually, he brought his baking traditions with him to East Chicago, Indiana, where he worked at Martinez-LeGrand’s great-grandfather’s bakery and met his future wife.

Where to start researching your family history:

- You can find information in databases or county courthouses, like probate records, census data or birth and death certificates. Remember to search for women using maiden names.

- There are 41 affiliated sites of familysearch.org in Indiana, where you can do research in person. The free database is run by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- Martinez-LeGrand often helps Mexican families search for baptism records because the information is usually recorded a few days after birth and lists grandparents. You can find those using familysearch.org or ancestry.com, though you may have to pay to get a record to the U.S.

How to safely store family photos and documents:

- Keep them inside in a spot with regular heat – not a basement, garage or attic. “Think of them as like a living object – or a houseplant,” she said. “Would they survive in your garage or your attic? No.”

- Use a pencil to write on the back of photos, not a pen, which could seep through the front.

- If you put a photo in an album, try not to use adhesive. If you decide to take them out later, it’s easier to tear a photo held in place with glue. Store those albums in acid-free boxes.

- Some libraries and historical societies will take documents and photos you don’t want to store, but call first to find out if they will accept what you have. If it doesn’t fit in their collection’s era or topic, they may not take it. For example, the Indiana Historical Society doesn’t take old newspapers.