Child welfare cases soar within Indiana’s heroin epidemic

INDIANAPOLIS (WISH) – Heroin is being blamed on the soaring number of children entering Indiana’s child welfare system, an I-Team 8 investigation uncovered.

More than 20,000 children fell under the watch of the state in 2015 – the highest total in eight years, according to an I-Team 8 review of Department of Child Services records. That figure easily eclipsed 2014’s total of more than 16,000 cases. Child welfare cases, which are often referred to as “child in need of services” or “CHINS” cases in Indiana, are many times spurred, experts say, by addicted parents who either end up in jail or are in drug treatment programs where they can’t care for their children.

“It was difficult,” said Jamie, an Indianapolis mother who asked not have her full name revealed.

She lost temporary custody of her eldest daughter for nearly a year while she was in drug treatment.

“My mom doesn’t quite understand that the easy part is getting off the drugs from the physical standpoint. The other standpoint is mental – because I had years of use – I used when I was happy, excited, lonely. It didn’t matter. To learn how to function without the use of drugs was the battle,” she said.

As part of the investigation, I-Team 8 analyzed state data on child welfare cases and conducted interviews with more than a dozen stakeholders – from addicts to judges, parents to defense attorneys and drug treatment counselors.

While there is some debate among them about whether there is a single cause linked to these increased caseloads, the consensus remains the same – heroin is part of the equation and the drug’s choking grip on Indiana is suffocating a child welfare system already overburdened.

“I think in no small way that’s a huge problem – is the drug usage,” said Mary Beth Bonaventura, the director of Indiana’s Department of Child Services. “Children are remaining in care longer than they used to be and it’s a direct correlation of people not being able to recover from addiction.”

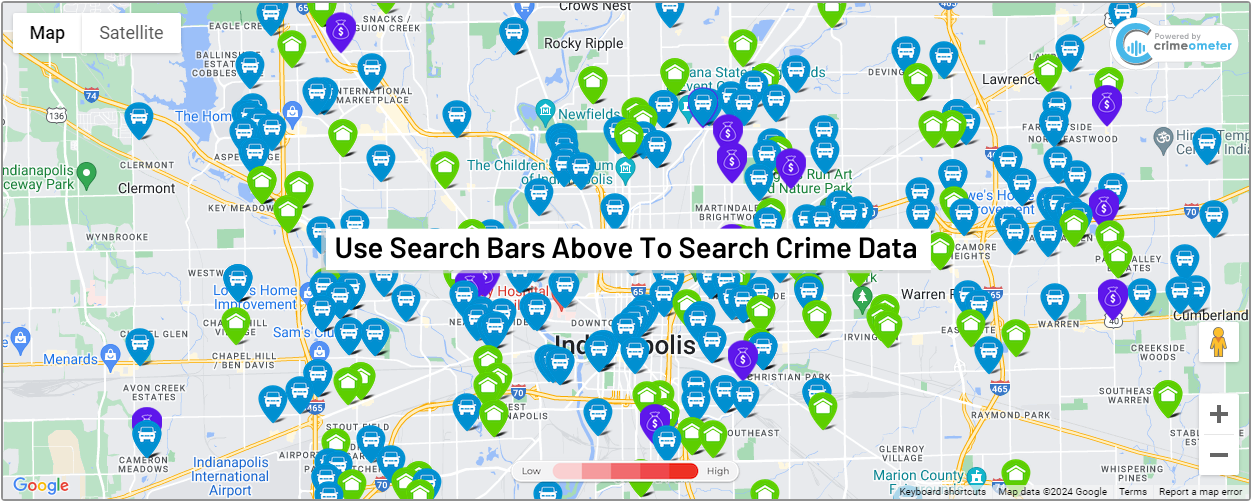

Nowhere is the problem more apparent than in Marion County, which had 3,800 child welfare cases in 2015, up from 2,300 cases just five years ago.

The increased caseloads have left the Department of Child Services looking to hire additional social workers.

DCS workers often act as prosecutors in CHINS cases. In turn, county public defenders like Bob Hill in Marion County have had to hire additional defense attorneys who can defend addicted parents in court during CHINS cases – where they are in danger of losing custody of their children while they’re in jail or in drug treatment.

“Yes, and what I’m saying is we are not doing a very good job of keeping our head above the water because of the increased caseloads,” Hill told I-Team 8.

Hill said he hired five additional defense attorneys in 2015 just to keep up with the increased caseloads.

Neil Weisman, the deputy chief public defender in St. Joseph County, said his county is also overwhelmed.

“We are getting more and more cases and we are approaching a point where we are out of compliance,” Weisman said in an interview with I-Team 8.

The fear with falling “out of compliance” with caseload maximums raises constitutional questions about whether these defense attorneys are providing adequate legal counsel to these indigent clients.

“This increase of 20 to 25 percent… frankly, I’m scared for my clients,” said David Shircliff, a defense attorney, during a recent meeting of the Indiana Public Defender Commission.

If more and more Indiana county public defenders fall out of compliance with caseload maximums, those counties stand to lose out on millions of dollars that are normally reimbursed by the state for representing indigent clients in child welfare cases.

In December, the Indiana Public Defender Commission voted to increase the caseload maximums to help counties like Marion stay in compliance. More specifically, public defenders who were previously told they can handle up to 120 child welfare cases are now being told they can handle up to 150, depending on staffing levels.

Hill and other public defenders raised questions about whether the increase in caseloads was directly tied to heroin or increased drug use. Most of those defense attorneys interviewed were of the belief that the DCS’s hiring of more case managers created more cases.

But Bonaventura disputes that.

“It’s quite the contrary,” she told I-Team 8. “We’ve added additional staff because the numbers have risen.The addiction problem is nationwide frankly, not just in Indiana.”The fuzzy numbers

The difficulty with getting an accurate read on how many of CHINS cases are actually tied to heroin is due in part to confidential nature of the case files. But in interviews with more than a dozen judges, attorneys, DCS employees, addicts and their families, the general consensus did not sway from the fact that opiate drugs are indeed partly to blame.

Making matters more confusing is that Indiana lacks a centralized public defender office. Each county is responsible for tracking its own caseloads which are then submitted to Indiana Public Defender Commission.

According to Derrick Mason, a staff attorney for the commission, some counties were counting both CHINS cases and termination of parent rights cases as one case. That skewed the numbers slightly, Mason said. So in an effort to get a more uniformed result the commission voted in December to start counting termination of parental rights cases and CHINS cases separately.

Termination of parental rights cases are just that – legal cases where the state strips away parental rights from a person.

Termination cases often start off as CHINS cases, Mason pointed out.

I-Team 8 took a closer look at the counties in central Indiana and discovered that termination of parental rights occurred in one out of every five CHINS cases in Marion and the surrounding “doughnut” counties in 2015. In Marion County alone, 763 parents lost their children last year.

At The Children’s Bureau – Indianapolis’ only shelter for children – CEO Tina Cloer said her agency has more than doubled in size in three years, something she equates in part to the struggle with addictions.

“We know from our records that roughly 65 percent of the kids that we get are coming from a home that is affected by addictions,” she said. “It’s traumatic for somebody come and remove you from your home and take you to a place with nobody that you know. So I think we try to be very mindful that the kids are the victims. It’s not their fault that they are in the system.A face of addiction

As she sat in her Indianapolis apartment holding her infant daughter, a woman named Jamie relived the low points of a years-long battle with heroin.

“I used when I was happy, sad, excited, lonely. It didn’t matter. To learn how to function without the use of drugs was the battle,” Jamie told I-Team 8.

Her battle included living in a hotel for nearly a year. Her boyfriend would burglarize homes to pay the hotel bill.

The rest, she says, they would spend on drugs.

Jamie, who requested that I-Team 8 not reveal her identity, spent time in jail for theft and endured two stints in a court-appointed drug treatment program before she was finally able to get clean.

It was during her treatment that Jamie lost temporary custody of her eldest daughter.

After pleading guilty to a theft and serving four months in jail, Jamie was able to get clean through a court-appointed drug treatment program.

But after suffering a relapse on heroin, Jamie called a court administrator to confess.

“Within a day, DCS was at my house,” she said.

While social workers filed a CHINS case against her, Jamie saw the ordeal as a blessing. It provided her with the opportunity to attend an in-patient treatment facility. She even credits the program with helping her stay clean for nearly two years.