Convicted hit man’s escape evokes mob’s ‘ruthless’ heyday in one American city

(CNN) — Dominic Taddeo was in his early 20s when a US Justice Department lawyer appeared before a Senate subcommittee with a dire warning about the future mafia hit man’s hometown.

“Rochester, the home of Kodak, Xerox, and other thriving corporations … is a wealthy city, a ripe plum ready to be plucked by the strongest and most ruthless mob,” Gregory Baldwin, an attorney with the department’s organized crime and racketeering section, said during the 1980 hearing.

In the upstate New York city, the mob was known for detonating homemade bombs by remote control under the cars of rivals, according to Baldwin’s testimony and news reports.

But Taddeo plied his deadly trade in the 1980s with a more conventional weapon — a .22-caliber pistol.

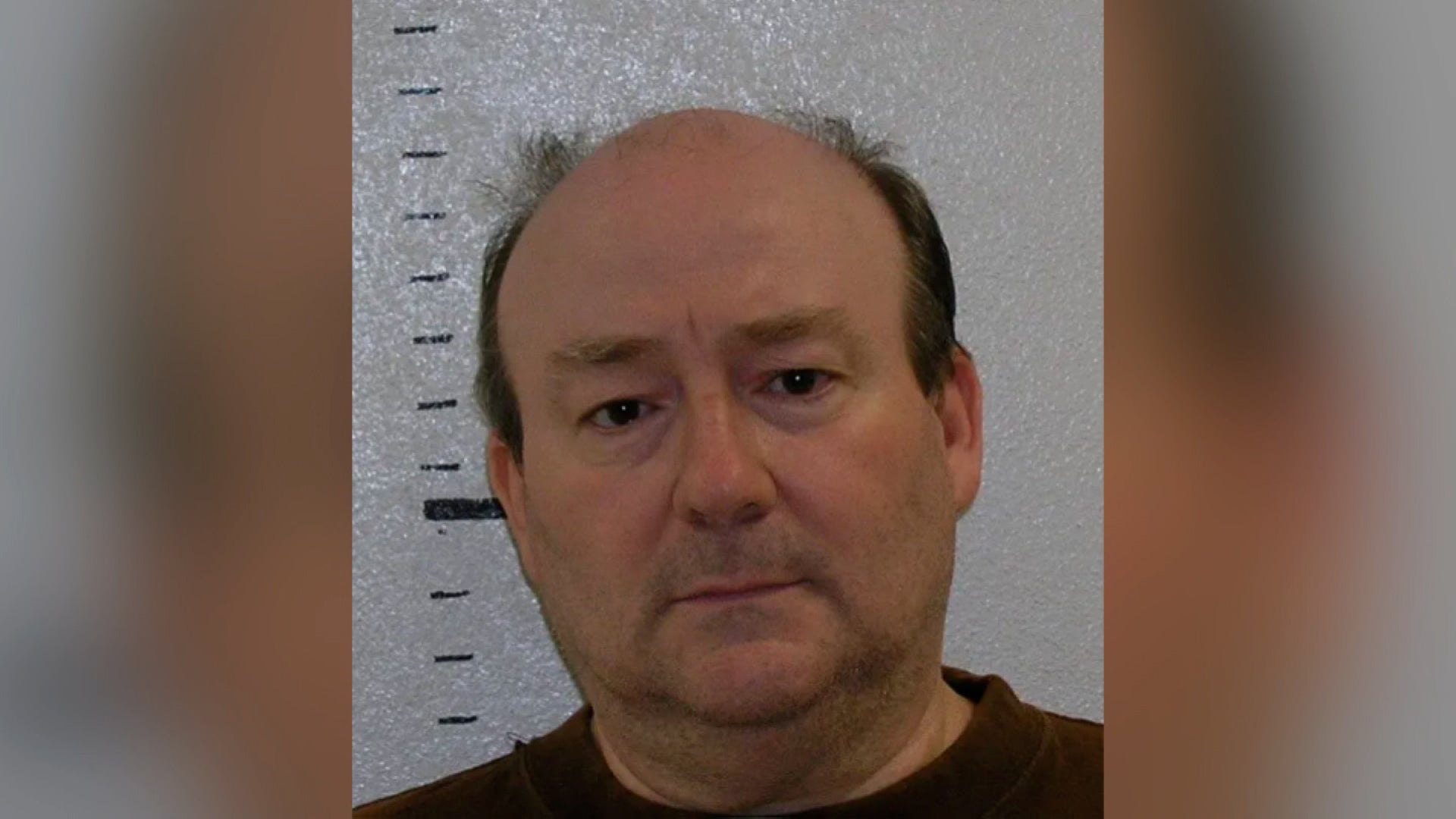

A man who federal officials say began a life of crime at the age of 16, Taddeo, 64, was a largely forgotten crime figure until his March 28 escape — less than a year before his likely release — from a Florida halfway house while on a medical appointment.

His short-lived breakout took mob observers back to the heyday of La Cosa Nostra in the Lake Ontario city of about 200,000 — where the tragicomedy antics of rival factions at times evoked the third-rate mobsters in Jimmy’s Breslin’s novel “The Gang that Couldn’t Shoot Straight.”

“I’m just not sure which side couldn’t shoot straight,” Baldwin, 75, now in private practice, said in an interview. “I mean, both sides shot themselves in the foot at some point.”

‘Who does that?’

Taddeo served more than three decades in prison after a conviction on racketeering charges that a federal judge said involved “the murder of three individuals, attempted murder of two more individuals, and conspiracy to murder a fifth person” as a mafia hit man.

The murders of Nicholas Mastrodonato, Gerald Pelusio and Dino Tortatice, in 1982 and 1983, were carried out on behalf of the Rochester mob, according to published reports.

Taddeo pleaded guilty to the shootings in January 1992, court records show. The plea included twice attempting to fatally shoot a mob boss and plotting to kill another gangster.

A federal judge sentenced Taddeo to 24 years in prison, which he was to serve consecutively to the 30 years he was already serving on other charges.

Taddeo was nearing the end of several prison sentences on assorted crimes that included illegal weapons possession, drug conspiracy and bail jumping, court documents show.

He was transferred in mid February to a halfway house in Orlando, from a medium security prison in Sumter County, Florida, according to Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). Taddeo was to be released next February, according to court documents.

Longtime mob observers were baffled that Taddeo did not return after his medical pass last month, especially with his supervised release expected in February.

“Who does that?” asked Blair Kenny, who has written several books about organized crime in Rochester. “There’s something wrong. Who knows? It’s erratic behavior.”

Gary Jenkins, an ex-detective who investigated the mob in Kansas City, said the brief escape didn’t surprised by him.

Jenkins noted that Taddeo was implicated in 1990 in what federal prosecutors believed was a bizarre scheme to break a Colombian drug lord out of prison and sell him to the Medellin cartel. The Morning Call newspaper in Allentown, Pennsylvania, described the alleged plot, which involved a weapons cache, camouflage gear and thousands of dollars in cash hidden in a storage locker.

“This guy has delusions of grandeur,” said Jenkins, host of the Gangland Wire Crime Stories podcast, which in December featured Taddeo and the Rochester crime family. “That’s an audacious dude… I mean he was obviously a planner.”

Taddeo had been on the run before. In 1987, facing federal weapons charges, he disappeared while out on bail and was arrested two years later after a national manhunt.

Court records show Taddeo has been appointed an assistant federal public defender but that attorney is not identified, according to the US Attorney’s Office for the Middle District of Florida. Taddeo’s former federal public defender in Rochester did not return a call seeking comment, and neither did his sister — who lives in Florida, along with their elderly mother.

Taddeo sought release during pandemic

It’s unclear how much planning went into Taddeo’s breakout but he was back in federal custody one week later.

“I was surprised he got caught so quick,” Jenkins said. “I figured he had something lined up to really get loose.”

US Marshals said he was apprehended without incident in Hialeah in Miami-Dade County.

Taddeo was indicted on an escape charge by a federal grand jury in Orlando, according to court documents. The maximum penalty is a five-year sentence.

The escape came after Taddeo sought a compassionate release in December 2020, citing the dangers the Covid-19 pandemic posed to his health. A federal judge denied the request and refused to reduce Taddeo’s sentence, noting the “seriousness of his offenses and his extremely lengthy criminal record.”

“Defendant began a life of crime at 16 years old,” U.S. District Judge Frank Geraci Jr. wrote in his decision last year.

“His prior convictions are for crimes including assault, conspiracy to distribute controlled substances and, most notably, Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization conspiracy arising from his employment and association with Rochester’s La Cosa Nostra organized crime family.”

The judge denied the release despite what he said was Taddeo’s “relatively clean disciplinary record” and claim that “he has learned his lesson” and desire “to play a positive role in his community.”

Bloody war for control of Rochester’s rackets

Taddeo was in his late teens and early 20s when, according to Baldwin’s Senate testimony, the Rochester organized-crime family was cashing in big time on a number of rackets, including gambling, loan sharking and arson-for-hire schemes.

“Rochester was a remarkably wealthy community at the time,” Baldwin said in the interview with CNN. “Back then it was the headquarters for Kodak, IBM, Stromberg Carlson, Bausch and Lomb. It made the city richer. And when the city gets richer, the pickings are better.”

But the prosperity was being undermined by a bloody war for control of the city’s lucrative rackets. Local papers dubbed it the “Alphabet Wars” — with a cadre of older, machine gun toting gangsters known as Team A facing off against a younger Team B with a penchant for remote controlled explosives, according to Baldwin’s testimony. One group had the backing of the New York mob; the other was supported by mafia figures in Buffalo and Pittsburgh.

At the time, the use of bombs and detonating devices was new to the mob.

“People get beat up. Legs would be broken. But a bomb in a car. That was just unheard of,” Baldwin said. “I don’t think I ever heard of any other mob cases — at least while I was in the (organized crime) strike force — that involved that kind of violence.”

On Columbus Day in 1970, a Rochester mob underboss ordered that a series of dynamite bombs be set off in the early morning hours in houses of worship and government buildings. The goal was to divert the attention of law enforcement efforts to radical groups of the time, Baldwin testified.

“The plan was to blame it on hippies or antiwar protesters,” he said in the interview. “I mean, none of it made a great deal of sense… The Columbus Day bombings, that was so inept it was almost a Keystone comedy. I mean they had bombs that probably couldn’t have blown off a two-year-old’s hand.”

Over time, however, the bomb makers got better though their bungling ways persisted. Baldwin’s Senate testimony chronicled the numerous plans to kill a Team A underboss with explosives.

One proposal involved secreting an explosive device in a Big Wheel tricycle and leaving it outside the mobster’s home. Baldwin said the plan was abandoned because of concerns about a child walking away with the toy.

“The concern for the safety of the child was not paramount, but the loss of the device was inexcusable,” he told the Senate, noting that each bomb cost more than $350 to make.

Another plan involved lowering a remote controlled bomb down the chimney of the gangster’s apartment. At the last minute they discovered the apartment had no chimney. Still another attempt had them using a magnet to attach a bomb to the exhaust pipe of a car but the device fell off during a running gun battle, according to Baldwin. A 12-year-old boy later found the bomb on the street.

“The bomb fell off because of the slush and the ice under the car,” Baldwin recalled in the interview. “It wasn’t connected cleanly enough. It’s a miracle that kid wasn’t killed. Witnesses said somehow, with his teeth, the boy pulled the blasting cap off the plastic explosive device. He should have bought a lottery ticket that day.”

Mob presence not ‘near the way it used to be’

In April 1978, Team B finally succeeded in killing the underboss with a bomb that exploded under his car.

The bloodletting for control of the Rochester rackets continued for years. Kenny, the writer of mob books, described Taddeo as a “short lived hit man” who preferred a .22-caliber pistol over improvised explosive devices during the height of his infamy in the 1980s.

Today, the Rochester mob, like La Cosa Nostra crime families around the nation, is a shadow of its former self. Federal crackdowns and state regulation of gaming have taken a toll. Members have broken the code of silence and disappeared into witness protection programs. Others have been killed — or died of old age. Still others, like Taddeo, have been convicted and locked away for years.

“I know they’re still around,” Kenny said of the mob, adding that, for a week, Taddeo was a reminder of the heyday of organized crime families.

“There’s definitely still a presence, but I don’t see the mob as anything near the way it used to be. I mean, if you’re from Rochester, you definitely know Dominic Taddeo.”