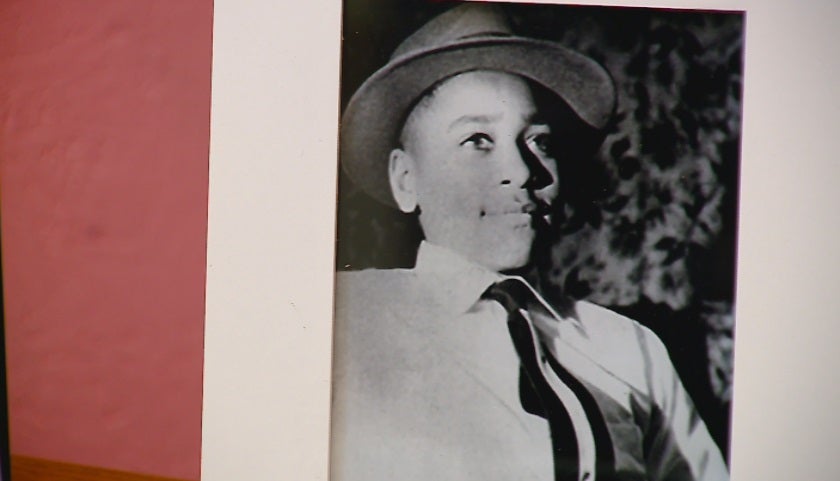

Emmett Till’s cousin recounts what happened in Bryant’s Grocery in 1955

Stories like Emmett Till’s are entrenched in American history. His death lit an important fire to the jolt of the American Civil Rights Movement.

Growing up, I learned details of Till’s life and death, and its impact, which most do not get to experience.

This week, you’ll get the “INside story” from Wheeler Parker Jr., Till’s cousin, and from Dan Wakefield, an Indianapolis native and award-winning writer and journalist. They painted a much-needed, vivid picture that still rings impactful nearly 70 years later.

(WISH) — Emmett Till, affectionately called “Bobo,” was a charming and verbocious 14-year old-boy from the Chicago suburb of Argo. He loved to make others laugh and was the apple of his mother and grandmother’s eyes.

In 1955, Parker was set to go to Mississippi to spend the summer with family and help work the land. That’s when Emmett’s desire to also experience summertime in Mississippi became an innocent urge to be “just one of the boys.”

“(Emmett) found out I was going and he went ballistic! Because he didn’t have any siblings. Plus, Emmett was a privileged child and only child. His grandma doted on him, his mama, everybody. ‘Bobo, Bobo.’ When his mother took him places, she also took me along. Fishing trips, wherever. We were going together, so we can became friends like that,” Parker said.

Mamie Till was hesitant to let her son Emmett go to Mississippi, mainly because the way of life and social expectation had great difference between the South and the North in the 1950s. Emmett had spent his whole life in Chicago. His mother, on the other hand, had lived in the South and knew what to expect.

“They didn’t want him to go because they knew what could happen. If you never live down South, you had no idea. Even if I tell you the story, you have no idea what it was like,” Parker said. “He was an excited kid. He loved fun and excitement. You know, he just he enjoyed life.”

On Aug. 20, 1955, Mamie rushed Emmett to the 63rd Street station in Chicago to catch the train to Money, Mississippi, to spend time with family.

The next day, Emmett arrived in Mississippi alongside Parker.

“In the South where we lived, when it was cotton-picking time, you better be in somebody’s field. So, we got there — it was fun to me because I had picked before I left — Emmett didn’t care too much for the cotton. It was too hot,” Parker said.

Three days after their arrival, Emmett joined his cousins for a trip to Bryant’s Grocery & Meat Market after a long day of working in the fields. The store was owned by a white couple, Roy and Carolyn Bryant. Most of their customers were Black.

“My uncle, he was 16 years old and had access to a car. To us, to me and Bobo, this is really exciting. We could hardly get a bicycle!” Parker said. “We went to the store, just about three miles away, because that’s where we got together after picking cotton. That’s where we met up. People hung outside the store, played checkers and talked. The biggest thing in the South was telling a jokes.

“I got to the store and for after a while I decided I wanted to get something, so I went in to buy. I went in and got something, and I remember very vividly … he (Emmett) came in while I was in there. I saidm ‘Man, I hope Emmett got it.’ I knew it was the South. That was my formative years. I stayed there until I was about 8 years old. They tell you want to do to stay alive,” Parker said.

“So I left and absolutely nothing happened. My uncle Simeon came in after me. He was 12, and Emmett was 14. I was 16,” Parker said. “The boy (Emmett) stuttered all the time. I don’t know if he was in there for a minute by himself. Uncle Simeon popped in. We knew the rules. They came out. Nothing happened in there. Nothing happened. He loved to make people laugh. So she came by it’s not like she come up or she didn’t come out in no rage or nothing.”

“It was normal. When she came out — she went that way past us and Emmett whistled. He whistled in the store to clear up his stutter. To say ‘bubble gum’. This time – this whistle was a wolf whistle,” Parker said. “That was making a statement. That was way out of line. More out line that you can imagine … I am telling you. We knew it. He didn’t know. He saw that we were afraid and then he became afraid. We just made a beeline for the car. We knew that he had violated a serious (unwritten) law.”

“Man, we got out of there! We are going down this dirt gravel road. Dust was flying everywhere, and a car was behind us! He said, ‘Man, they are after us … they are after us!’ I thought, ‘How could they be after us already?’ My uncle sped up of course. We stopped the car and ran through the cotton fields,” Parker said.

This is the first of a five-part series discussing the murder of Till and his impact on American history.