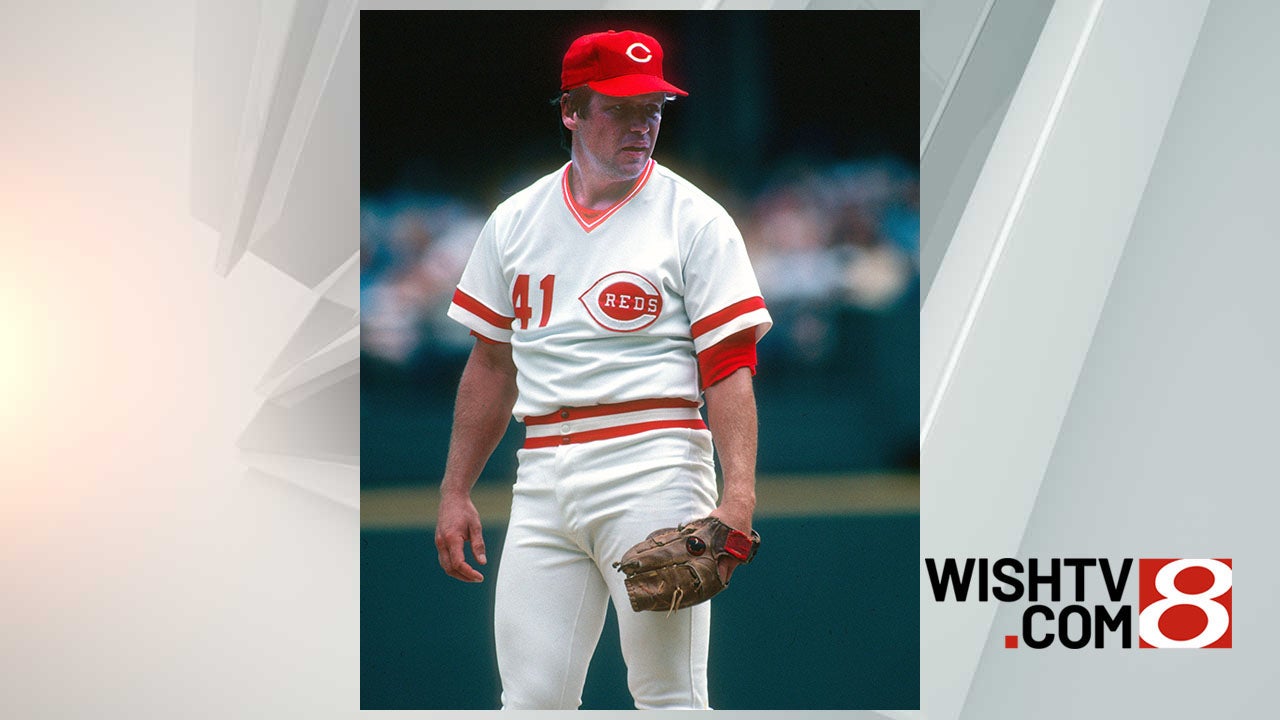

Hall of Fame pitcher Tom Seaver dies at 75

NEW YORK (AP) — Tom Seaver transformed a franchise and captivated a

city, setting enduring standards as he whipped his powerful right arm

overhead for the Miracle Mets and dirtied his right knee atop major

league mounds for two decades.

A consummate pro and pitching icon, he finished fulfilled after a career remembered with awe long after his final strikeout.

“It

is the last beautiful flower in the perfect bouquet,” Seaver said on

the afternoon he was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame.

Seaver,

the galvanizing force who steered the New York Mets from the National

League cellar to a stunning World Series title in 1969, has died. He was

75.

The Hall said Wednesday night that Seaver died Monday from

complications of Lewy body dementia and COVID-19. Seaver spent his final

years in Calistoga, California.

Seaver’s family announced in

March 2019 he had been diagnosed with dementia and had retired from

public life. He continued working at Seaver Vineyards, founded by the

three-time NL Cy Young Award winner and his wife, Nancy, in 2002 on 116

acres at Diamond Mountain in the Calistoga region of Northern

California.

Seaver was diagnosed with Lyme disease in 1991, and

it reoccurred in 2012 and led to Bell’s Palsy and memory loss, the Daily

News of New York reported in 2013.

“He will always be the heart

and soul of the Mets, the standard which all Mets aspire to,” Mike

Piazza, a former Mets catcher and Hall of Famer, tweeted when Seaver’s

dementia diagnosis was announced.

Nicknamed Tom Terrific and The

Franchise, Seaver was a five-time 20-game winner and the 1967 NL Rookie

of the Year. He went 311-205 with a 2.86 ERA, 3,640 strikeouts and 61

shutouts during an illustrious career that lasted from 1967-86. He

became a constant on magazine covers and a media presence, calling

postseason games on NBC and ABC even while still an active player.

“He

was simply the greatest Mets player of all-time and among the best to

ever play the game,” Mets owner Fred Wilpon and son Jeff, the team’s

chief operating officer, said in a statement.

Seaver was elected

to the Hall of Fame in 1992 when he appeared on 425 of 430 ballots for a

then-record 98.84%. His mark was surpassed in 2016 by Ken Griffey Jr.,

again in 2019 when Mariano Rivera became the first unanimous selection

by baseball writers, and in 2020 when Derek Jeter fell one vote short of

a clean sweep.

“Tom was a gentleman who represented the best of

our national pastime,” Commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement. “He

was synonymous with the New York Mets and their unforgettable 1969

season.”

“After their improbable World Series championship, Tom

became a household name to baseball fans — a responsibility he carried

out with distinction throughout his life,” he said.

Seaver’s

plaque in Cooperstown lauds him as a “power pitcher who helped change

the New York Mets from lovable losers into formidable foes.” He changed

not only their place in the standings but the team’s stature in people’s

minds.

“Tom Seaver hated to lose,” said Jerry Grote, his longtime

catcher with the Mets. “In May of 1969, we had a celebration in the

locker room when we reached .500 for the first time. Tom said, ‘We want

more than .500, we want a championship.’”

Seaver pitched for the

Mets from 1967-77, when he was traded to Cincinnati after a public spat

with chairman M. Donald Grant over Seaver’s desire for a new contract.

It was a clash that inflamed baseball fans in New York.

“My

biggest disappointment? Leaving the Mets the first time and the

difficulties I had with the same people that led up to it,” Seaver told

The Associated Press ahead of his Hall induction in 1992. “But I look

back at it in a positive way now. It gave me the opportunity to work in

different areas of the country.”

He threw his only no-hitter for

the Reds in June 1978 against St. Louis and was traded back to New York

after the 1982 season. But Mets general manager Frank Cashen blundered

by leaving Seaver off his list of 26 protected players, and in January

1984 he was claimed by the Chicago White Sox as free agent compensation

for losing pitcher Dennis Lamp to Toronto.

While pitching for the

White Sox, Seaver got his 300th win at Yankee Stadium and did it in

style with a six-hitter in a 4-1 victory. He finished his career with

the 1986 Boston Red Sox team that lost to the Mets in the World Series.

“Tom

Seaver was one of the best and most inspirational pitchers to play the

game,” Reds Chief Executive Officer Bob Castellini said in a statement.

“We are grateful that Tom’s Hall of Fame career included time with the

Reds. We are proud to count his name among the greats in the Reds Hall

of Fame. He will be missed.”

Supremely confident — and not

necessarily modest about his extraordinary acumen on the mound — Seaver

was a 12-time All-Star who led the major leagues with a 25-7 record in

1969 and a 1.76 ERA in 1971. A classic power pitcher with a

drop-and-drive delivery that often dirtied the right knee of his uniform

pants, he won Cy Young Awards with New York in 1969, 1973 and 1975. The

club retired his No. 41 in 1988, the first Mets player given the honor.

“From

a team standpoint, winning the ’69 world championship is something I’ll

remember most,” Seaver said in 1992. “From an individual standpoint, my

300th win brought me the most joy.”

Seaver limited his public

appearances in recent years. He did not attend the Baseball Writers’

Association of America dinner in 2019, where members of the 1969 Mets

were honored on the 50th anniversary of what still ranks among

baseball’s most unexpected championships.

Five months later, as

part of a celebration of that team, the Mets announced plans for a

statue of Seaver outside Citi Field, and the ballpark’s address was

officially changed to 41 Seaver Way in a nod to his uniform number.

Seaver did not attend those ceremonies, either, but daughter Sarah Seaver did and said her parents were honored.

“This

is so very appropriate because he made the New York Mets the team that

it is,” said Ron Swoboda, the right fielder whose sprawling catch helped

Seaver pitch the Mets to a 10-inning win in Game 4 of the ’69 Series

against Baltimore. “He gave them credibility.”

Seaver’s death was announced, in fact, hours after the Mets beat the Orioles in an interleague game.

“Just

a class act. Just a gentleman in the way he handled himself, and really

the way handled his whole career,” said Miami manager Don Mattingly, a

former New York Yankees captain. “We just left New York, and every time

you walk in a door there, it’s like Tom Seaver Hall, with different

pictures.”

When the Mets closed their previous home, Shea Stadium,

on the final day of the 2008 regular season, Seaver put the finishing

touches on the nostalgic ceremonies with a last pitch to Piazza, and the

two walked off together waving goodbye to fans.

He is survived by Nancy, daughters Sarah and Anne, and grandsons Thomas, William, Henry and Tobin.

George

Thomas Seaver was born in Fresno, California, on Nov. 17, 1944, a son

of Charles Seaver, a top amateur golfer who won both his matches for the

U.S. over Britain at the 1932 Walker Cup.

Tom Seaver was a star

at the University of Southern California and was drafted by Atlanta in

1966. He signed with the Braves for $51,500 only for Commissioner

William Eckert to void the deal. The Trojans already had played

exhibition games that year, and baseball rules at the time prohibited a

club from signing a college player whose season had started. Any team

willing to match the Braves’ signing bonus could enter a lottery, and

Eckert picked the Mets out of a hat that also included Cleveland and

Philadelphia.

Among baseball’s worst teams from their expansion

season in 1962, the Mets lost more than 100 games in five of their first

six seasons and had never won more than 73 in any of their first seven

years. With cherished Brooklyn Dodgers star Gil Hodges as their manager,

a young corps of pitchers led by Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Gary Gentry and

a still-wild Nolan Ryan, and an offense that included Cleon Jones and

Tommie Agee, the Mets overtook the Chicago Cubs to win the NL East with a

100-62 record in 1969.

They swept Hank Aaron and the Atlanta

Braves in the first NL Championship Series to reach the World Series

against highly favored Baltimore, which had gone 109-53. Seaver lost the

opener 4-1 in a matchup with Mike Cuellar, then pitched a 10-inning

six-hitter to win Game 4, and the Mets won the title the following

afternoon.

Seaver was an All-Star in each of his first seven

seasons. Aaron introduced himself to Seaver at the pitcher’s first

All-Star Game in 1967.

“Kid, I know who you are, and before your career is over, I guarantee you everyone in this stadium will, too,” Aaron said.

For Seaver, that All-Star appearance made him feel like he belonged.

“I may have been paid before, but that’s when I really became a professional,” he said.

Perhaps

Seaver’s most memorable moment on the mound was at Shea Stadium on July

9, 1969, when he retired his first 25 batters against the Chicago Cubs.

Pinch-hitter Jimmy Qualls looped a one-out single to left-center in the

ninth inning before Seaver retired Willie Smith on a foulout and Don

Kessinger on a flyout.

“I had every hitter doing what I wanted,”

Seaver recalled in 1992. “Afterward, my wife was in tears and I remember

saying to her: ‘Hey, I pitched a one-hit shutout with 10 strikeouts.

What more could I ask for?’”