Why Willie Mays, not Babe Ruth, was baseball’s greatest player

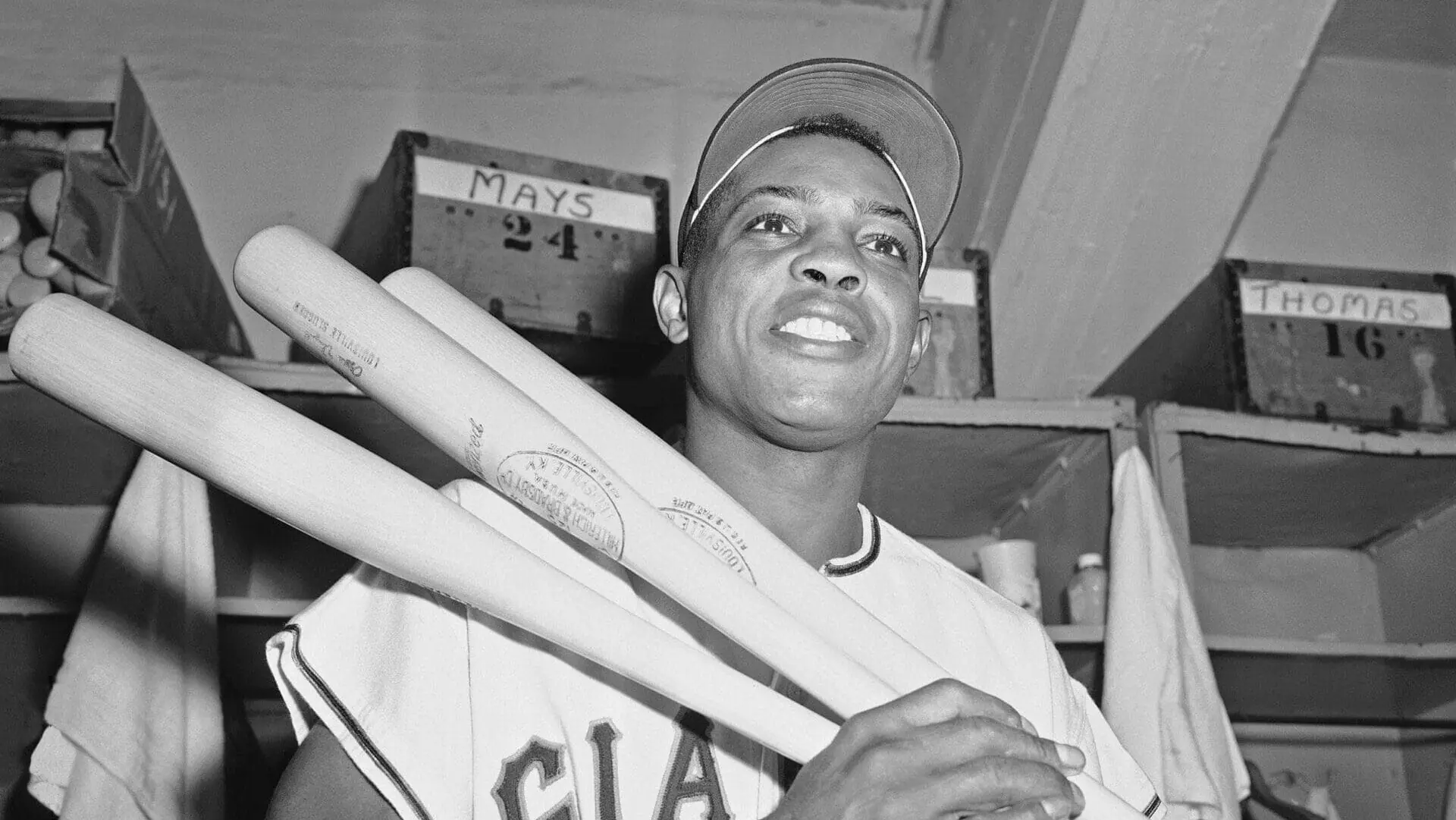

New York (CNN) — Among students of baseball, there has long been widespread belief that Willie Mays was the game’s greatest all-around player.

That might come as a surprise to those who are casual fans, or not fans at all, when they read obituaries this week that describe Mays, who died Tuesday at the age of 93, as the greatest. Babe Ruth was the common answer to the game’s “greatest player” title starting more than 100 years ago, when he smashed home run records and lifted the popularity of the game to the point it became known as the national pastime. And Ruth’s exploits as a Herculean slugger came after part of his career was as one of baseball’s top pitchers, making him a rare two-way great.

But Mays achieved greatness in many more aspects of the game than Ruth, even if he never threw a pitch.

“Willie Mays was the player who did everything better than anybody else,” said sportswriter Joe Posnanski. “That’s not to say he did every single thing better. Maybe he was not the greatest baserunner. But he was one of the best. Maybe not the greatest hitter, but again, one of the best. One of the best fielders. You put all of those things together and you have the most perfect player who ever lived.”

Posnanski, whose 2021 best selling book “The Baseball 100” ranked the game’s greatest players, ranked Mays as No. 1 and Ruth as No. 2.

There is a term in baseball to describe Mays’ rare kind of greatness — “a five-tool player,” one who can hit for average, hit for power, field, throw and run.

“I don’t know if they invented the term to describe him. But he epitomized it like no one else,” said Jayson Stark, a baseball writer for The Athletic and a member of the writer’s wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Stark wrote an appreciation of Mays on Thursday, citing 22 different little-known statistics that demonstrate Mays’ greatness. Stark noted that Mays is the only player to ever lead his league in all 10 of these key offensive categories: hits, runs, home runs, triples, stolen bases, batting average, on base percentage, slugging percentage total bases and walks.

Mays is also the only player with more than 300 home runs, 300 stolen bases, 3,000 hits and a lifetime .300 batting average — all milestone marks in the sport.

But even Stark acknowledges the numbers don’t really do Mays justice.

“I honestly don’t think you need to tell this story of Willie Mays with the numbers,” he said.

Many who cite his greatness also speak about the joy he brought to the game.

“Baseball is a game that is meant to be enjoyed, and there has never been a player more joyful than Willie Mays,” said Posnanski.

“There was a sense of joy and charisma that was unmatched,” said Stark. “He could turn millions of people into baseball fans by himself.”’

Ruth was also a larger than life player who packed stadiums, popularizing the home run to almost single-handedly change the way the game was played. But there was something about how happy Mays was on the field that captured the public’s imagination in a different way. His greeting to people, “Say hey!” led to his nickname the Say Hey Kid. And he always seemed to be a kid playing a child’s game at a great level, throughout a career that lasted 23 years.

‘The catch’

And as great a hitter as Mays was, the most famous moment of his career might have come in centerfield at the Polo Grounds in New York, where his Giants played before moving to San Francisco in 1958. In the first game of the 1954 World Series, against a heavily favored Cleveland team, he caught a fly ball an estimated 425 feet from home plate, with his back to the plate, and then wheeled and threw the ball back to the infield in one motion to stop a runner from scoring.

It is widely talked about as the greatest catch in the history of the game, even though Mays himself said he made numerous catches that were better. Stark said when he quoted longtime baseball announcer Vin Scully as saying during the 1992 World Series that a catch the previous day by Toronto Blue Jays centerfielder Devon White had been better, it caused an outcry. People wouldn’t accept there could be a better catch than Mays’ catch. Even White said his catch couldn’t be compared to Mays’ catch. White’s catch was soon widely forgotten, while Mays’ catch is still discussed and referred to regularly by fans nearly 70 years after the fact.

“The Willie Mays catch will always be its own thing,” said Posnanski.

“Name any other player with 600 home runs whose most famous play is a catch,” said Stark. “That just doesn’t happen.”

Mays played more games in center field than any other player in history and caught more balls in the outfield. He threw out nearly 200 baserunners from the outfield. But defense is still not as appreciated by some fans and statistical measures as offensive ones, says Gary Gillette, a baseball historian and editor of The Baseball Encyclopedia. He said it’s one of the reasons that Mays’ greatness isn’t as fully appreciated as it should be.

“Whether you create a run or prevent a run, you’re helping your team to win equally,” he said.

Respecting important intangibles

Gillette says Mays also had one key edge over Ruth when comparing their accomplishments: Ruth played in a segregated era and therefore didn’t compete against the best Black ballplayers. Mays was one of the players who helped integrate baseball in the 1950s, starting his career in 1951 just four years after Jackie Robinson broke the game’s disgraceful color barrier.

“Very few people try to adjust for (Ruth’s career in a segregated game),” said Gillette.

Mays also didn’t play in most of the 1953 season or any of the 1954 season while serving in the Army in Korea. In the 1955 and 1956 seasons, he hit 41 and 51 home runs, respectively, suggesting he would have totaled well over the 55 home runs in two lost seasons to overtake Ruth’s then-record 714 career home runs. It would therefore be Hank Aaron, not Mays, to be the first to eclipse Ruth as the home run leader.

“(Mays’) 660 home runs was great, but it wasn’t more than Babe,” said Gillette.

So Mays’ greatness was often not fully appreciated, especially by casual fans. He played most of his career on the West Coast, depriving fans in much of the country from following his success. He only played in four World Series, spread out across his 23-year career. And of course he played in the era before ESPN and highlight shows on cable and the internet, which is how many of today’s fans follow the game.

“The brilliance of Mays day-to-day in the ’50s and ‘60s is practically lost,” said Steve Hirdt, a longtime baseball statistician and historian and senior director of operations and research at Stats Perform. “They were on television, but there was no preservation of most of those broadcasts. The lack of film or video tape when he was at his peak leave current day fans with an incomplete picture of how great he was.”

Hirdt is actually one of the baseball historians who gives an edge to Ruth over Mays because of Ruth’s success as a pitcher. But he says Mays is a very close second in overall greatness. And while he never saw Ruth play, Hirdt says he cherishes the games he saw Mays play.

“Willie was the most exciting player I’ve ever seen, and there’s no one close for second,” he said.