Dr. Obeime works tirelessly on behalf of underinsured

INDIANAPOLIS (WISH) — Dr. Mercy Obeime knew she wanted to help other people, and she knew she would use medicine to do that.

But what she didn’t realize is that her degree from Indiana University was not only going to make a difference here in Indiana, but many thousands of miles away.

“Poverty is a huge reason that people have poor health,” said Obeime. “And that’s one of the reasons that people do not address their health issues.”

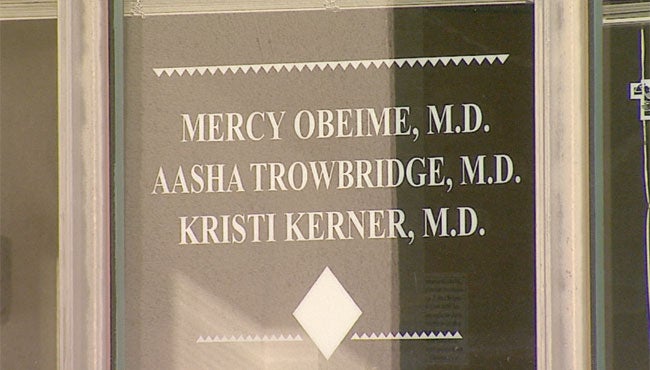

Dr. Obeime, has been practicing medicine on the south side of Indianapolis for about 20 years at the Saint Francis Neighborhood Health Center. The majority of her patients are uninsured, something Obamacare has impacted.

“We have more patients with insurance, but having an insurance card unfortunately doesn’t solve a lot of the problems,” said Obeime.

Getting people in is easy, but getting them to get their prescriptions and to follow up, is not so easy. That’s why Obeime stresses that getting the under-insured preventive care not only costs taxpayers less to treat them, but it’s vital to the health of her client’s whole family.

“Patients who get really sick, who lose everything, end up on Medicaid,” said Obeime.

Because poverty is not a circumstance that can be treated by a doctor, Obeime has worked with lawmakers here and in D.C., to help impact policy. Her desire to treat the whole person, is what motivates her practice.

Obeime’s center has a Marion County “baby shop” inside, where clients get coupons that can be used to buy necessities for their babies. She also felt called to help those in need in her native Nigeria. In 2001, she started the Mercy Foundation, and for many years she took medical mission trips to see patients there. It’s a way to combine her faith and career, by addressing the basic need in every person.

“Sometimes people don’t even want you to fix everything,” said Obeime. “They just want you to listen, they want you to listen and say ‘yes, I know that this hurts, I know that it is difficult to live in this situation.’”

For Obeime, helping those around her see and understand just how much she cares is part of the job; and by addressing the whole person, not just their physical ailments, she is able to do that.

“Whether it is here, or whether it is on our medical missions, people just want to be cared for, most people (want to feel) loved,” she said. “You cannot treat somebody by just saying where it hurts. They may be hurting spiritually, emotionally or socially and if those things are not addressed, you’re not going to get a good outcome.”