Lupus and other autoimmune diseases strike far more women than men. Now there’s a clue why

WASHINGTON (AP) — Women are far more likely than men to get autoimmune diseases, when an out-of-whack immune system attacks their own bodies — and new research may finally explain why.

It’s all about how the body handles females’ extra X chromosome, Stanford University researchers reported Thursday — a finding that could lead to better ways to detect a long list of diseases that are hard to diagnose and treat.

“This transforms the way we think about this whole process of autoimmunity, especially the male-female bias,” said University of Pennsylvania immunologist E. John Wherry, who wasn’t involved in the study.

More than 24 million Americans, by some estimates up to 50 million, have an autoimmune disorder — diseases such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and dozens more. About 4 of every 5 patients are women, a mystery that has baffled scientists for decades.

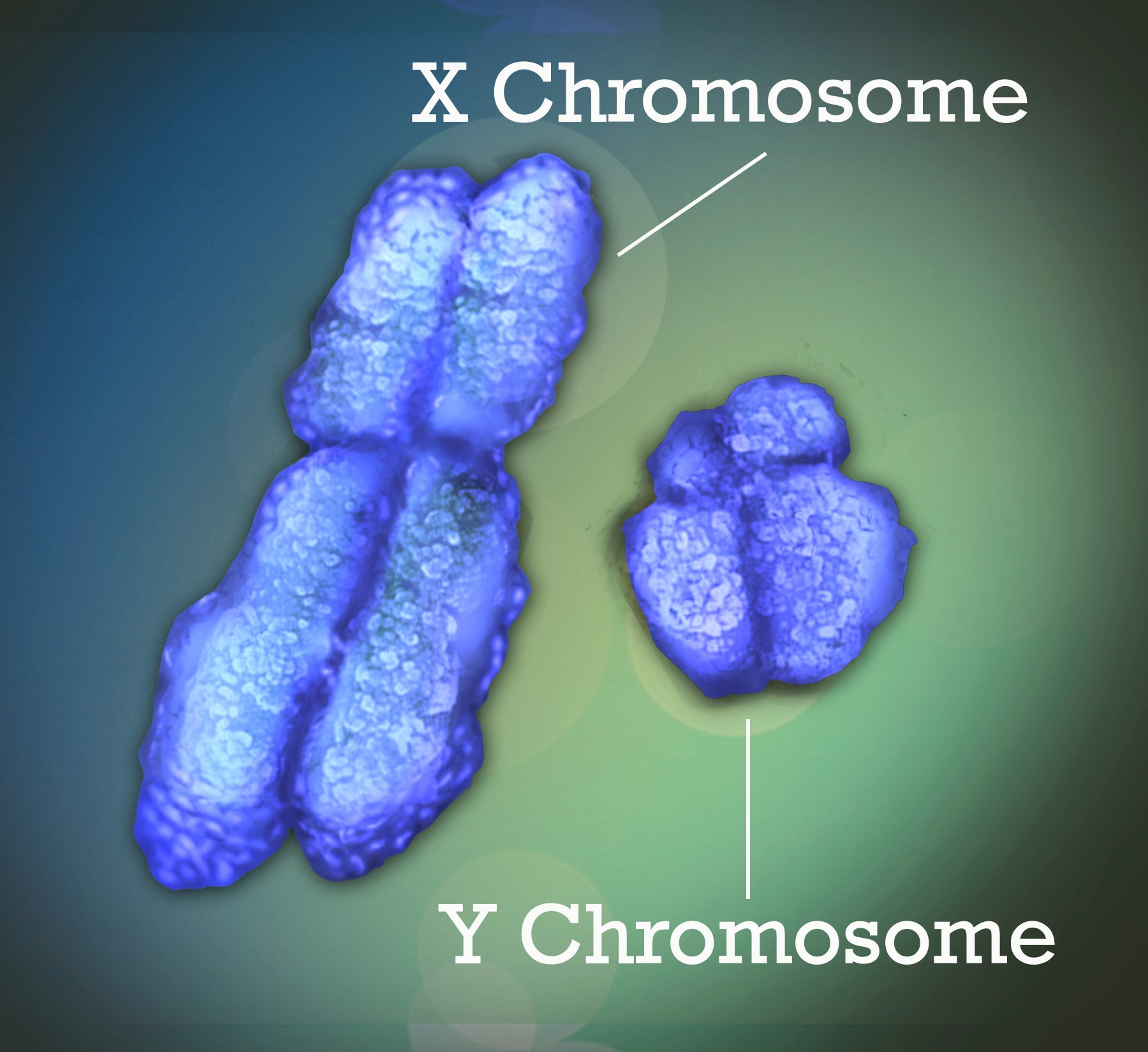

One theory is that the X chromosome might be a culprit. After all, females have two X chromosomes while males have one X and one Y.

The new research, published in the journal Cell, shows that extra X is involved — but in an unexpected way.

Our DNA is carried inside each cell in 23 pairs of chromosomes, including that final pair that determines biological sex. The X chromosome is packed with hundreds of genes, far more than males’ much smaller Y chromosome. Every female cell must switch off one of its X chromosome copies, to avoid getting a toxic double dose of all those genes.

Performing that so-called X-chromosome inactivation is a special type of RNA called Xist, pronounced like “exist.” This long stretch of RNA parks itself in spots along a cell’s extra X chromosome, attracts proteins that bind to it in weird clumps, and silences the chromosome.

Stanford dermatologist Dr. Howard Chang was exploring how Xist does its job when his lab identified nearly 100 of those stuck-on proteins. Chang recognized many as related to skin-related autoimmune disorders — patients can have “autoantibodies” that mistakenly attack those normal proteins.

“That got us thinking: These are the known ones. What about the other proteins in Xist?” Chang said. Maybe this molecule, found only in women, “could somehow organize proteins in such a way as to activate the immune system.”

If true, Xist by itself couldn’t cause autoimmune disease or all women would be affected. Scientists have long thought it takes a combination of genetic susceptibility and an environmental trigger, such as an infection or injury, for the immune system to run amok. For example, the Epstein-Barr virus is linked to multiple sclerosis.

Chang’s team decided to engineer male lab mice to artificially make Xist — without silencing their only X chromosome — and see what happened.

Researchers also specially bred mice susceptible to a lupus-like condition that can be triggered by a chemical irritant.

The mice that produced Xist formed its hallmark protein clumps and, when triggered, developed lupus-like autoimmunity at levels similar to females, the team concluded.

“We think that’s really important, for Xist RNA to leak out of the cell to where the immune system gets to see it. You still needed this environmental trigger to cause the whole thing to kick off,” explained Chang, who is paid by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which also supports The Associated Press’ Health and Science Department.

Beyond mice, researchers also examined blood samples from 100 patients — and uncovered autoantibodies targeting Xist-associated proteins that scientists hadn’t previously linked to autoimmune disorders. A potential reason, Chang suggests: standard tests for autoimmunity were made using male cells.

Lots more research is necessary but the findings “might give us a shorter path to diagnosing patients that look clinically and immunologically quite different,” said Penn’s Wherry.

“You may have autoantibodies to Protein A and another patient may have autoantibodies to Proteins C and D,” but knowing they’re all part of the larger Xist complex allows doctors to better hunt disease patterns, he added. “Now we have at least one big part of the puzzle of biological context.”

Stanford’s Chang wonders if it may even be possible to one day interrupt the process.

“How does that go from RNA to abnormal cells, this will be a next step of the investigation.”