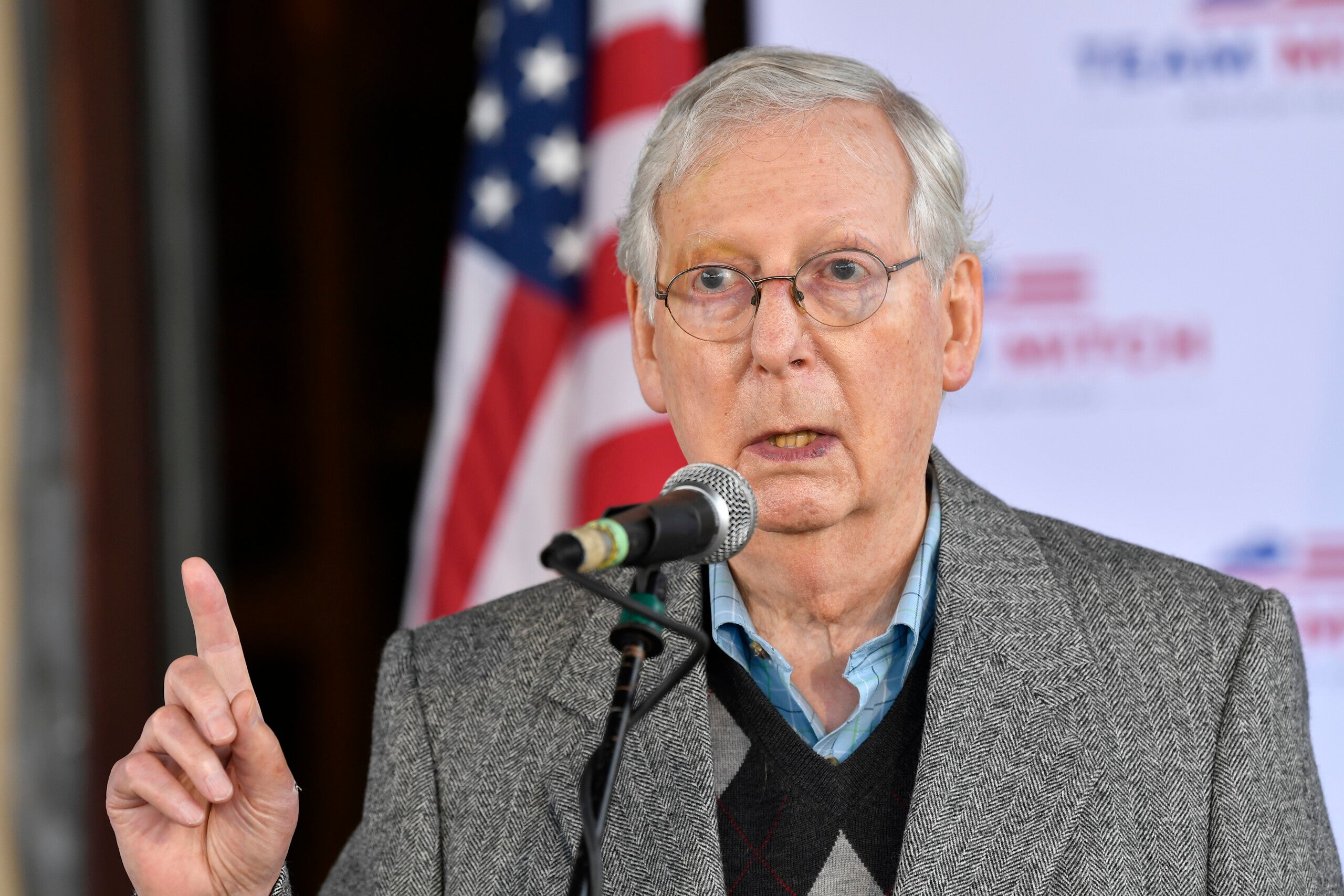

Senate GOP leader McConnell sticking with partisan COVID-19 relief plan

WASHINGTON (AP) — Top Senate Republican Mitch McConnell said Tuesday he’s largely sticking with a partisan, scaled-back COVID-19 relief bill that has already failed twice this fall, even as Democratic leaders and a bipartisan group of moderates offered concessions in hopes of passing pandemic aid before Congress adjourns for the year.

The Kentucky Republican made the announcement after President-elect Joe Biden called upon lawmakers to pass a downpayment relief bill now with more to come next year. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi resumed talks with Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin about a year-end spending package that could include COVID relief provisions. Key Senate moderates rallied behind a scaled-back framework.

It’s not clear whether the flurry of activity will lead to actual progress. Time is running out on Congress’ lame-duck session and Donald Trump’s presidency, many Republicans won’t even acknowledge that Trump has lost the election and good faith between the two parties remains in short supply.

McConnell said his bill, which only modestly tweaks an earlier plan blocked by Democrats, would be signed by Trump and that additional legislation could pass next year. But his initiative fell flat with Democrats and a key GOP moderate.

“If it’s identical to what (McConnell) brought forth this summer then it’s going to be a partisan bill that is not going to become law,” said Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, who joined moderates in unveiling a $908 billion bipartisan package only hours earlier. “And I want a bill that will become law.”

Democrats declined to release details of their concessions to McConnell.

“Speaker Pelosi and I sent him the proposal in a good faith effort to start, to get him to negotiate in a bipartisan way,” Schumer said.

McConnell’s response was to convene conversations with the Trump team and House GOP Leader Kevin McCarthy of California. During the campaign, Trump appeared eager to sign a relief bill and urged lawmakers to “go big” but McConnell said Tuesday’s modest measure is all he’ll go for now.

“We don’t have time for messaging games. We don’t have time for lengthy negotiations,” McConnell said. “I would hope that this is something that could be signed into law by the president, be done quickly, deal with the things we can agree on now.” He added that there would still be talks about “some additional package of some size.”

McConnell’s reworked plan swiftly leaked. A summary ignores key demands of Democrats and moderates such as aid to states and local governments and additional unemployment benefits.

In Wilmington, Delaware, Biden called on lawmakers to approve a down payment on COVID relief, though he cautioned that “any package passed in lame-duck session is — at best — just a start.”

And a bipartisan group of lawmakers proposed a split-the-difference solution to the protracted impasse over COVID-19 relief in a last-gasp effort to ship overdue help to a hurting nation before Congress adjourns for the holidays. It was a sign that some lawmakers across the spectrum are reluctant to adjourn for the year without approving some COVID aid.

The group includes Senate centrists such as Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., and Collins, who hope to exert greater influence in a closely divided Congress during the incoming Biden administration.

The proposal by the bipartisan group hit the scales at $908 billion, including $228 billion to extend and upgrade “paycheck protection” subsidies for businesses for a second round of relief to hard-hit businesses like restaurants. It would revive a special jobless benefit, but at a reduced level of $300 per week rather than the $600 benefit enacted in March. State and local governments would receive $160 billion, and there is also money for vaccines.

Previous, larger versions of the proposal — a framework with only limited detail — were rejected by top leaders such as Pelosi, D-Calif., and McConnell. But pressure is building as lawmakers face the prospect of heading home for Christmas and New Year’s without delivering aid to people in need.

Lawmakers’ bipartisan effort comes after a split-decision election delivered the White House to Democrats and gave Republicans down-ballot success. At less than $1 trillion, it is less costly than a proposal meshed together by McConnell this summer. He later abandoned that effort for a considerably less costly measure that failed to advance in two attempts this fall.

“It’s not a time for political brinkmanship,” Manchin said. “Emergency relief is needed now more than ever before. The people need to know that we are not going to leave until we get something accomplished.”

Pelosi and Mnuchin were discussing COVID relief and other end-of-session items, including a $1.4 trillion catchall government funding bill. Mnuchin told reporters as he arrived at a Senate Banking Committee hearing to assess earlier COVID rescue efforts that he and Pelosi are focused primarily on the unfinished appropriations bills, however.

“On COVID relief, we acknowledged the recent positive developments on vaccine development and the belief that it is essential to significantly fund distribution efforts to get us from vaccine to vaccination,” Pelosi said afterward.

Pelosi and Mnuchin grappled over a relief bill for weeks before the November election, discussing legislation of up to $2 trillion. But Senate GOP conservatives opposed their efforts and Pelosi refused to yield on key points.

The bipartisan compromise proposal is virtually free of detail, but includes a temporary shield against COVID-related lawsuits against businesses and other organizations that have reopened despite the pandemic.

That’s a priority for McConnell. But his warnings of a wave of destructive lawsuits haven’t been borne out, and it is sure to incite opposition from the trial lawyers’ lobby, which retains considerable influence with top Democratic leaders.

The centrist lawmakers, both moderates and conservatives, billed their proposal as a temporary patch to hold things over until next year. It contains $45 billion for transportation, including aid to transit systems and Amtrak, $82 billion to reopen schools and universities, funding for vaccines and health care providers, and money for food stamps, rental assistance and the Postal Service.