Experts worry suspensions create school-to-prison pipeline

INDIANAPOLIS (WISH) – One out of every five Indianapolis Public School students were given out-of-school suspensions last year.

In other words, more than 6,000 students last year were kicked out of the classroom.

An I-Team 8 investigation found there’s a growing concern among academia and legal experts that the high rate of suspensions in Indianapolis might be creating more criminals. Some worry that by kicking students out of class, school districts might be further exacerbating the so-called school-to-prison pipeline.

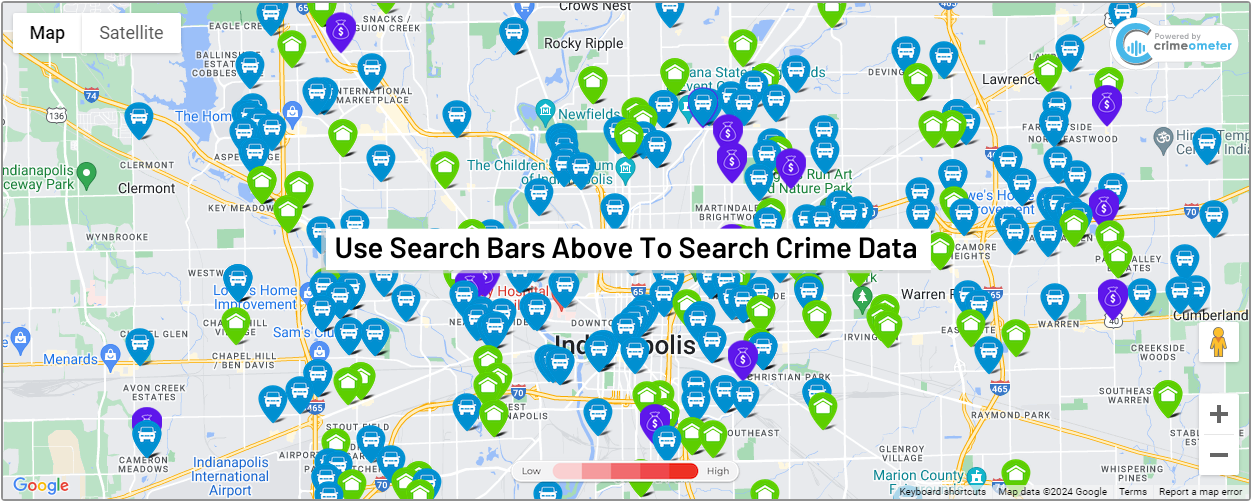

Search Marion County School Discipline Records (2011-2013)

New research by an Indiana University professor suggests schools that often suspend students create a punitive environment that results in lower test scores among all students.

“What our research suggests is that suspension is not good for anyone. This idea that we should use suspension to create this better learning environment – we are not seeing that at all in our data,” said IU sociology professor Brea Perry in an interview with I-Team 8.

Perry’s research, done while she was at the University of Kentucky, was recently published in the American Sociological Review. It examined the same students attending a large urban school district in Kentucky over the course of several years. What Perry and her research partner discovered is that reading and math scores of all students lowered when suspensions were up.

“I think I can say with certainty that kids in these highly punitive environments perform worse,” Perry told I-Team 8.By the numbers

An I-Team 8 analysis of school records showed IPS handed out-of-school suspensions to more than 5,400 students in the 2012-2013 school year*. Last school year, that figure grew to more than 6,000. Disciplinary records within the district are broken down by 17 categories that included reasons for suspensions and expulsions. They include things like alcohol, drugs, weapons, fighting, profanity and violence among others.

(*Our analysis found an anomaly in discipline records on the state department of education’s website and numbers provided to I-Team 8 by IPS. State records show there were approximately 3,600 students given out-of-school suspensions in the 2012-13 school year. IPS records show there were 5,495. However, both records indicate the percentage of students being suspended grew between the 2012-13 and 2013-2014 school years.)

In 2014, two combined categories of fighting and battery account for more than 2,200 of the out-of-school suspensions in IPS. The single highest category for suspension that year was defiance – with 1,941 suspensions.

(REPORT CONTINUES BELOW IMAGE)

When asked if the district is suspending too many children, Deborah Leser, IPS director of student services said: “I don’t think I can answer that, and I don’t think you’re going to find anybody who can answer that.”

In a follow-up question, when pressed about whether the number of students being suspended was acceptable, Leser said:

“Absolutely not. And we’ve worked very hard this year. We’ve actually decreased our disciplinary referrals over 40 percent this year.”

While IPS did provide I-Team 8 with disciplinary records for the 2012-13 and 2013-14 school years, the district did not have updated figures for this school year, nor did they allow our cameras access to any of their 67 schools despite repeated requests.

(REPORT CONTINUES BELOW TABLE)

2013-2014 Marion County Out-Of-School Suspensions

In our lengthy interview, Leser did acknowledge that the district is aware of its high rate of suspensions and said it is making strides to correct it by working to draft a code of conduct to serve as a guideline for students, parents and teachers on ways to correct behaviors that might result in an exclusionary suspension or expulsion.

Leser, a former teacher and principal now serving in the IPS central office, also said the IPS has sought to model its code of conduct after one adopted by a Fort Wayne school district, which she said has seen success and reduce its suspensions.

“Suspending a student doesn’t really do anything. It doesn’t really help anybody, it just puts them out of school. And when they come back those same problems are still there,” she said.

When asked why IPS still suspends so much, she replied: “Well, we have reduced our referrals by over 40 percent, so we are trying to remedy that.”

Creating criminals

Marion County’s top juvenile judge Marilyn Moores says juvenile court receives 1,500 care referrals from Marion County schools each year. Of those, 80 percent of them never lead to a conviction.

As a result, Moores has drafted a letter to all Marion County school superintendents telling administrators to stop “wasting” the court’s time by arresting students and referring them to court for discipline issues she feels should be handled at the school level.

“The resources need to be spent on the kids who pose a threat to public safety, not on kids who are driving adults crazy,” Moores told I-Team 8.

Moores says this habit creates a pipeline where students are being arrested and exposed to other children who might be a real threat to public safety. In other words, she thinks school districts might be bypassing the traditional principal’s office discipline method in favor or sending disruptive students straight to court.

“Data shows that exposing children to juvenile detention is a risk factor for kids,” Moores said.

When asked if she feared their exposure to the juvenile justice complex was creating criminals, she replied: “It’s not a fear; it’s fact. Data unequivocally shows that exposing low-level offenders to high-level offenders creates high-level offenders.”

A copy of the letter obtained by I-Team 8, reads in part: “The purpose of the juvenile court is to address delinquent behavior that impacts public safety. We are not part of the discipline policy/procedure of schools, and using court resources to process youth at the front end of the system who will never reach disposition is neither appropriate, nor effective.”

Moores said the time spent arresting students coupled with the additional resources of court and staff time is “wasted” as the court is committed to spending its resources on cases that put public safety at risk.

Moores told I-Team 8 while juvenile court will still accept case referrals from the school districts, it will not accept outright arrests for non-violent offenses.

She concludes her letter, in part, by saying: “The court is also committed to working with schools in Marion County to identify alternatives to arrest, suspension and expulsion.”

Youth in trouble or troubled youth?

One recent afternoon outside the Juvenile Justice Complex, I-Team 8 spoke to teens who were just being released from juvenile detention.

Among them was 17-year old Davon Davis, who said he had just spent three weeks behind bars for an issue he would not discuss.

“He got into the wrong crowd at the mall so here I am at the juvenile center,” his mother, Tasha Carter, said.

Davis, who said it was his first time being locked up, admitted it wasn’t his first time getting in trouble. He said he’s been suspended from school before and now attends alternative school.

“I really couldn’t recall (for) you how many times I’ve been suspended. I’d say at least three times,” Davis said.

Davis acknowledged when asked that he knew the suspensions were meant to deter misbehavior and correct his actions.

“But I think it’s no help,” he added. “They should do something else in school other than suspending kids … like in-school suspensions where they give you work.”

Another student, Robert Powell, said he had just spent three weeks in juvenile detention. A police report shows he was suspected in an armed robbery with a BB gun. His grandmother, Tammy Powell, said the case was dismissed after the witness failed to show up for court.

Robert Powell denied that he was involved. He did admit his troubles started in school, and that he had been previously suspended for skipping class and fighting.

“He’s angry. He has anger issues and doesn’t want to follow the rules,” Tammy Powell said. “Something happened to him.”

When pressed further, Tammy Powell explained that she had adopted the 14-year-old after his father, Robert Johnson, was convicted of fatally shooting Robert’s mother, Taminka Powell, in 2003.

“A lot of stuff has been going on. I’m angry. I don’t know why,” Robert told I-Team 8.

Leser says it is often issues at home that can cause flare ups at school or lead to student misbehavior.

“Discipline is a very individualize part of education, and we really have to look at each child to see what’s going on in that child’s world and what’s going on in the school and what’s going on that’s creating this situation where a child feels so frustrated or so upset that they react in that way,” Leser said.

I-Team 8 also spoke to a juvenile case coordinator, who asked to remain anonymous because the company she worked for did not permit to speak with reporters. She said clients she works with have been suspended for using profanity. Many, she says, end up being recommended for juvenile detention for non-violent crimes.

“They are not necessarily bad, they just have some behavioral issues. They’re kids. They don’t like authority,” she said. “It’s really not fair to them because they are not being reprimanded like they should. It’s being too harsh and then they get detained, and it’s just a repeating cycle.”

Racial disparity

Last fall, educators, doctoral students and civil rights advocates warned Indiana lawmakers that Indiana has a racial disparity when it comes to suspensions and expulsions.

Speaking before a panel of lawmakers of the Interim Study Committee on Education in September, educators pointed to national data that claimed Indiana suspends more black male students than any other state – tied only with Missouri. They also said state data from 2007-2012 shows that African-American students are consistently placed in both in-school and out-of-school suspension at higher rates than other ethnic groups.

Statistics like that, they say, can lead to possibly worse outcomes for students – such as increased drop-out rates and run-ins with crime.

Nate Williams, a doctoral candidate in education at IUPUI, told the panel that “historically, there is an over representation of African-American and students receiving special needs services” who are disciplined.

Carole Craig with both the Greater Indianapolis NAACP and the Children’s Policy and Law Initiative of Indiana warned that if Indiana’s current disparity is left unchecked, the state could run the risk of a federal intervention.

“Yes that does lead to a federal investigation by the federal government. And, of course, that’s already happened when it comes to special education and suspension,” Craig said when asked about the worst case scenarios.

But Craig coupled her statements with good news – that federal intervention can be avoided if schools and school districts take a proactive approach to adopting new discipline models. Some suggestions from her group have been increasing teacher and staff training, collecting better data on in-school and out-of-school suspensions, and exploring alternative methods to student discipline in lieu of suspensions and expulsions.

IPS records show out-of-school suspensions were issued to IPS students nearly 90 times more often than in-school suspensions in 2013-14. 392 students were expelled from IPS in the same time period.

One possible solution could be using the idea of “restorative justice,” which Williams explained involves talking to students about their adverse behaviors and addressing the problem with the student being disciplined.

Leser told I-Team 8 IPS is open to that model but that its proposed code of conduct would not be implemented until next school year.