Federal grand jury investigating Kansas City cop who allegedly ‘exploited and terrorized’ Black residents for decades

(CNN) — Federal prosecutors in Kansas have launched a criminal grand jury investigation into a retired Kansas City police detective who is the subject of long-swirling allegations that he “exploited and terrorized” Black residents of the city’s north end for decades.

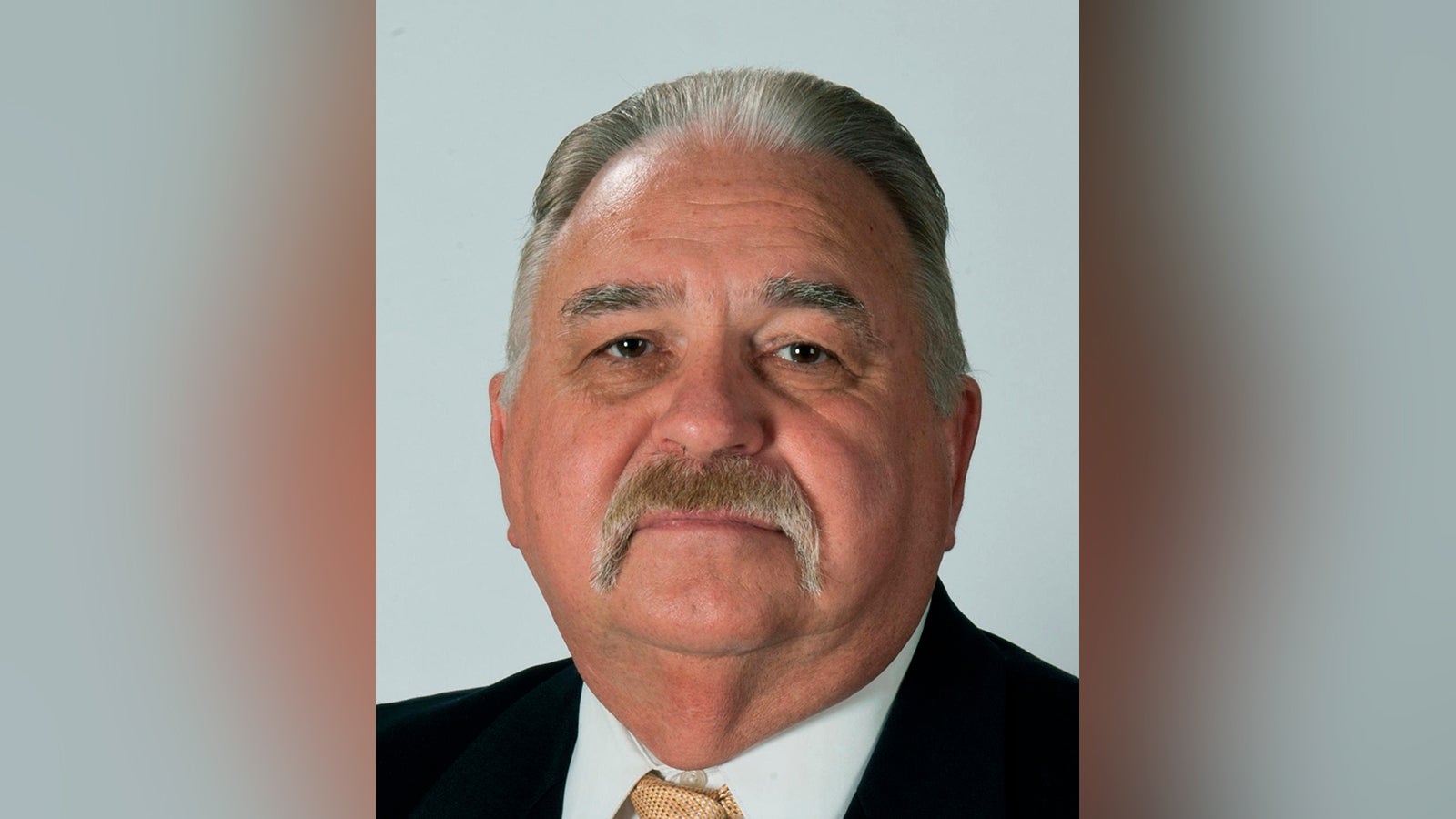

Roger Golubski is accused of being “a dirty cop who used the power of his badge to exploit vulnerable black women, including black women who worked as prostitutes,” according to a 2019 civil complaint filed by a man exonerated of double murder charges investigated by Golubski. The veteran detective, who retired from the Kansas City, Kansas, police department in 2010 at the rank of captain, was also accused of being on the payroll of a local drug kingpin and of framing people for crimes they did not commit.

The unproven allegations have roiled the community for years and recently attracted the attention of hip-hop mogul Jay-Z. The rapper’s social justice-oriented group, Team Roc, took out a full-page ad in the Washington Post last week calling the alleged police corruption in Kansas City “one of the worst examples of abuse of power in U.S. history.”

Golubski, 69, has not been charged with any crimes nor faced any discipline in connection with the highly public — and highly inflammatory — allegations against him. During a civil court deposition last year, he repeatedly invoked his constitutional right against self-incrimination, pleading the Fifth over and over again. An attorney representing Golubski in the civil case declined comment, citing the pending litigation.

While the city’s newspaper and police reform activists have been clamoring for action, prosecutors have been quietly calling witnesses to testify about Golubski since at least August, two sources familiar with the matter said.

Among those who testified is Terry Zeigler, a former chief of the department who spent three years as Golubski’s partner. Another officer summoned to testify is mentioned as a possible corroborating witness in the civil court deposition of a woman who accused Golubski of sexually assaulting her. A third officer called to testify purportedly walked in on Golubski during a sexual encounter with a woman in his office at the police station.

Federal authorities declined comment. Unlike witnesses, prosecutors are governed by strict secrecy rules governing grand jury proceedings. Without comment from prosecutors, CNN could not determine the full scope of the investigation, its focus or how many witnesses have been called.

Former partners

Zeigler said he spent roughly two hours before the grand jury in the Topeka, Kansas, federal courthouse last month answering questions about his role working homicide cases with Golubski from 1999 to 2002.

He said he told the panel he had previously worked in the department’s internal affairs unit and was unaware of Golubski’s purported reputation for misconduct. Zeigler, who retired from his job as chief in September 2019, said he never witnessed Golubski commit any crimes or sexual misconduct during their time together.

“They were trying to understand how I didn’t know or was I trying to cover up things about Roger that I knew,” Zeigler said. “I don’t mind talking and telling people because I don’t have anything to hide.”

Zeigler said he and Golubski did not socialize outside of work and that he had little insight into his personal life. He recalled one incident that he said raised his suspicions, telling the grand jury about once calling Golubski’s home in the middle of the night about a homicide that had just occurred. A woman answered the phone and said Golubski was not home. Moments later, when Zeigler got Golubski on the phone, Zeigler said the detective denied that there was any woman at his house. On another occasion, he said, he learned Golubski was getting married and that he had not been invited to the wedding, despite being his partner.

“The dude was very secretive,” Zeigler said. “I mean he would want you to talk all day about your family, but he would talk very little about his own.”

Zeigler said Golubski appeared despondent when the allegations against him became public, and the two met for breakfast at an IHOP restaurant.

“He was very emotional,” Zeigler recalled.

Zeigler said he did not take Golubski’s mental state to mean that he was guilty, but that he “had this black cloud over his name” that he felt he could do nothing to remove.

He said he encouraged Golubski to seek counseling but added that he had not seen him since that meeting.

Zeigler said he was aware of more than a half dozen former KCKPD officers who have either already testified or have been subpoenaed to appear this week before a grand jury. Zeigler said prosecutors had also subpoenaed approximately a dozen case files from the department in 2019 shortly before he retired. He said he did not know any details of the cases.

After leaving the KCKPD in 2010, Golubski worked for six years as a detective at a nearby department before retiring for good in 2016.

Zeigler said he was not privy to the details of the federal investigation but that, based on what he knows, he found the allegations against his former partner difficult to believe.

“I think everybody has a hard time believing that this could be true,” he said.

A ‘manifest injustice’

Golubski first came under public scrutiny in 2016 for his work in the double murder conviction of Lamonte McIntyre. McIntyre, who had served 23 years in prison, was freed in 2017 when the district attorney for Wyandotte County, which includes Kansas City, Kansas, concluded the case represented a “manifest injustice.”

McIntyre’s lawyers alleged in court documents that police and prosecutors conducted a shoddy investigation and intentionally manipulated witnesses to convict McIntyre for the crime. They also alleged that the entire trial and appeals process was tainted by an undisclosed years-old romantic relationship between the prosecutor, Terra Morehead, and the judge, J. Dexter Burdette.

The newly elected district attorney Mark Dupree, who came into office in January 2017 as a progressive criminal justice reformer, said he was taking no position on those allegations.

“Information has been presented over the last few weeks by Mr. McIntyre’s defense team and individuals in the community alleging misconduct on several levels of law enforcement,” Dupree said in a statement issued shortly after he asked a court to dismiss the case. “My office is not agreeing that any of those entities committed wrongdoing.”

Judge Burdette has remained silent on the issue — until now. In a recent interview, at his Kansas City home, he said that, at the time of the trial in 1994, he had no duty to disclose what he described as a brief, non-exclusive dating relationship that ended several years before the trial began. He said it had no bearing on the case and that he had no regrets about how he conducted himself, adding that he believed at the time that McIntyre received a fair trial. Morehead did not respond to requests for comment.

CNN reached out to Dupree’s office on multiple occasions for comment about the McIntyre case and related allegations against Golubski. He declined to be interviewed, and a spokesperson declined to respond to detailed written questions.

A year after his release from prison, McIntyre and his mother filed a civil lawsuit in federal court against multiple officers involved in his case, taking particular aim at Golubski. His misconduct, they argued, was not only permitted, but “endorsed and rewarded” by his superiors, including Zeigler. The complaint accuses Golubski of having sexually assaulted McIntyre’s mother, Rose, in the late 1980s and then framing her teenage son for a double murder because she rebuffed his continued pursuits.

In the years since McIntyre’s release, the allegations against Golubski have been closely covered in the local newspaper, the Kansas City Star. The paper’s editorial board has referred to him as a “lifelong criminal” and a prominent columnist wrote that he was “the common denominator” in the unsolved murders of a half dozen Black women.

In May, the editorial board urged the Department of Justice to get involved in the matter and “sweep away the web of lies that has allowed Golubski and others to escape punishment.” More recently, Jay-Z’s Team Roc filed a lawsuit against the KCKPD to obtain complaints of alleged misconduct against officers, including Golubski, dating back decades. The group also recently helped arrange $1 million in donations to The Midwest Innocence Project, which along with another nonprofit called Centurion Ministries and Kansas City attorney Cheryl Pilate, worked to overturn McIntyre’s conviction in 2017.

A fight for freedom

The allegations against Golubski are based in part on dozens of affidavits gathered by defense investigators during the years-long fight to win McIntyre’s freedom.

They include a woman who testified that she saw McIntyre commit the murders, but who later recanted her testimony, several family members of the victims who insist they believe McIntyre is innocent and others who said that a young enforcer from a local drug house was responsible for the slayings.

A main thrust of the documents, though, was that Golubski was a corrupt cop and had been for decades. One witness after another described him as being obsessed with Black female prostitutes and of using the power of his badge to extort them for sex and information. The civil lawsuit accused Golubski of being on the payroll of a local drug kingpin and giving him information and protection in exchange for cash and drugs that he would in turn use to ply his stable of prostitutes.

‘I suffered nightmares’

Lamonte McIntyre’s mother said in a 2014 sworn affidavit that Golubski preyed on her in the late 1980s. It began, she said, when he rousted her from a car she was sitting in with her then-boyfriend outside a nightclub. Golubski ordered her to get out of the car and join him in his police vehicle. He crudely propositioned her and threatened to arrest her boyfriend if she didn’t come to see him at the police station the following night, she said. Rose McIntyre said she feared the repercussions of ignoring a police officer, so she showed up there as he asked.

Once in his office, Rose McIntyre alleged, Golubski performed oral sex on her against her will. After that encounter, he began vigorously pursuing her, at times calling her up to three times a day. She eventually had to move and change her phone number to get rid of him, she said.

“This entire incident caused immense trauma,” Rose McIntyre said in her declaration. “In fact, I suffered nightmares about it for a long time.”

In April 1994, when her then 17-year-old son was arrested for the double homicide, Golubski was one of the main detectives on the case. A court transcript shows that she and Golubski each testified at the same juvenile court hearing two months after the arrest.

Rose McIntyre also attended her son’s trial in September at which Golubski was a key witness, though McIntyre said in her affidavit that she spent her time in the hallway because she’d been listed as a potential witness by both the prosecution and the defense.

McIntyre said in a recent deposition she first learned of Golubski’s involvement years later from James McCloskey, the founder of Centurion Ministries, a group devoted to clearing the wrongfully convicted. McCloskey was a key figure in reinvestigating Lamonte McIntyre’s case and a driving force in collecting the dozens of affidavits submitted in his defense.

“The timing of these allegations is suspicious,” Golubski’s civil defense attorneys wrote in a recent court filing. The lawyers are seeking additional details about conversations between Rose McIntyre and McCloskey “to ensure that information regarding Mr. Golubski, his alleged behavior, and alleged motives, was not leading or suggestive so as to unduly influence or affect Ms. McIntyre’s memory.”

From a murder investigation to marriage

Ethel Abbott, one of Golubski’s four ex-wives, was also among those who provided a sworn statement to Lamonte McIntyre’s attorneys.

In the document, and in a recent interview, Abbott said she was working at a gas station in the late 1980s where a homicide took place. Golubski was assigned to investigate the homicide and asked her to look at some security video footage to help identify the suspect, which Abbott said she did.

But after her involvement in the case should have ended, she said Golubski began to pursue her, even though she had a boyfriend. She eventually broke up with her boyfriend and married Golubski. Abbott said they had a normal life for a while, which included a post-marriage trip to New Orleans, melding their families and going to church on Sundays “like regular families do.”

But after a few years of marriage, she said, she began to hear rumors from friends and family in her childhood neighborhood in Kansas City’s north end — where Golubski often patrolled — that her husband was not being faithful. Once, she said, she caught him in the company of two women in his car who appeared to be prostitutes and later confronted him. Following the episode, and a comment in which he allegedly disparaged Black women as being “uneducated,” she said she got back at him by running up $50,000 in credit card debt and left him. He harassed her on and off for a decade, she said. At some point after they were divorced, she complained to the police department’s internal affairs office.

Both she and Golubski were present, she said, when a police official admonished Golubski that he’d be fired if he didn’t leave her alone. She said Golubski stormed out of the office but was never disciplined by the department.

Earlier this year, Abbott said, she was visited by two FBI special agents who inquired about her history with Golubski. She said they spent hours asking her questions and showing her photos of different women, some of them deceased. Among them was Rhonda Tribue whose unsolved 1998 murder prompted the FBI to offer a $50,000 reward for information earlier this year.

Abbott said the agents, at least one of whom was assigned to the agency’s public corruption squad, wanted to know if she’d seen Golubski with any of the women. She said she told them she had not. She said investigators from McIntyre’s defense team had years earlier asked about any unexplained assets during their marriage, and she said she had no information about that either.

In the interview, she described her former husband as a “chameleon” who was secretive about his finances and conducted his business in a private study to which she did not have access.

“He kept that locked,” she recalled. “That was none of my business.”