With Indiana’s next execution just 11 weeks away, clemency request is next move

INDIANAPOLIS (CONSUMER REPORTS) — Amid a surge of executions being carried out across the country, Indiana’s first death row inmate in more than a decade is scheduled to meet the same fate before the end of the year, barring a final act of clemency at the discretion of Gov. Eric Holcomb.

Joseph Corcoran, who killed four people in 1997, was ordered by the Indiana Supreme Court last month to be executed Dec. 18.

Although Corcoran’s attorneys have argued that he should be spared due to his mental illness, the state’s high court upheld the sentence, just as multiple state and federal courts have done, as well.

Larry Komp, lead attorney for Corcoran’s legal team, told the Indiana Capital Chronicle his client is seeking a last plea with a clemency petition, however. Komp said he plans to visit with Corcoran — who’s currently being held at the Indiana State Prison— and file the necessary paperwork this week.

During the clemency process, Komp said the goal is to engage with the governor and his legal advisers as much as possible “to facilitate the most accurate decision.”

Holcomb has so far defended the state’s move to carry out Corcoran’s execution, saying he would let the legal process “play out” but review any petition materials that make it to his desk. Although the state parole board leads the clemency process, it’s up to the governor to issue a final verdict.

Corcoran’s mental health has been a part of the decades-old case since its inception, with state and federal public defenders saying he continues to suffer from paranoid schizophrenia that causes him to experience “persistent hallucinations and delusions.” Komp was unable to comment on recent conversations with his client, but emphasized that Corcoran “continues to suffer from a serious mental illness.”

Komp and other counsel focused on Corcoran’s mental state in their most recent filings with the state supreme court and are likely to double down in the clemency petition.

“They continue to administer major antipsychotic drugs,” Komp said. “Indiana State Prison has not cured his schizophrenia.”

Death row inmates in five states were put to death in the last 10 days — an unusually high number of executions that defies a yearslong trend of decline in the United States.

The first execution was carried out on Sept. 20 in South Carolina. Two more death row inmates, in Missouri and Texas, were pronounced dead last week following executions.

Death warrants were additionally carried out last week in Alabama and Oklahoma, marking the first time in more than 20 years — since July 2003 — that five executions were held in seven days, according to the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center.

Six other U.S. executions are scheduled before Corcoran’s December date. The next is set for Tuesday, in Texas.

Another Indiana man, Benjamin Ritchie, could be on deck. Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita filed a motion with the state’s high court last week requesting an execution date be set for the death row inmate, who was convicted in 2002 for killing a law enforcement officer from Beech Grove.

Ritchie has exhausted his appeals. It’s now up to Indiana’s high court justices to grant the state’s request and set an execution date.

Indiana’s execution process

Since 1897, all of Indiana’s 92 state executions have taken place at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, as required by state law.

While separate from state death warrants, an additional 16 executions have been carried out at the federal prison in Terre Haute since 2001.

Including Corcoran, eight men currently sit on death row — also called “X Row” — in Indiana.

State code requires executions to be carried out by lethal injection and take place “before the hours of sunrise” on the date scheduled by the Indiana Supreme Court.

The warden of the state prison is responsible for selecting an executioner. State law does not stipulate who can administer life-ending drugs. The Indiana Department of Correction did not answer the Capital Chronicle’s request for information about who has been, or could be, selected for Corcoran’s execution.

Although multiple individuals are involved in the Indiana execution process, their identities have historically been kept confidential, as instructed under the law.

Death row inmates are provided with a last, or “special” meal, ordered from a local restaurant, according to DOC. The meal must be eaten within four hours and is served 48 to 36 hours before the execution. An inmate is allowed to share food with visitors.

Matthew Wrinkles, the last to be expected in Indiana in December 2009, was served prime rib with a loaded baked potato, pork chops with steak fries and two salads with ranch dressing and rolls, the Times of Northwest Indiana reported.

Also during the final 48 hours, offenders are permitted unrestricted phone calls to say their goodbyes. They’re also allowed to visit with family, friends and lawyers in two-hour intervals.

Shortly before execution, inmates are further able to write down a final statement. They’re given the chance to provide one last verbal statement in the minutes before the lethal injection.

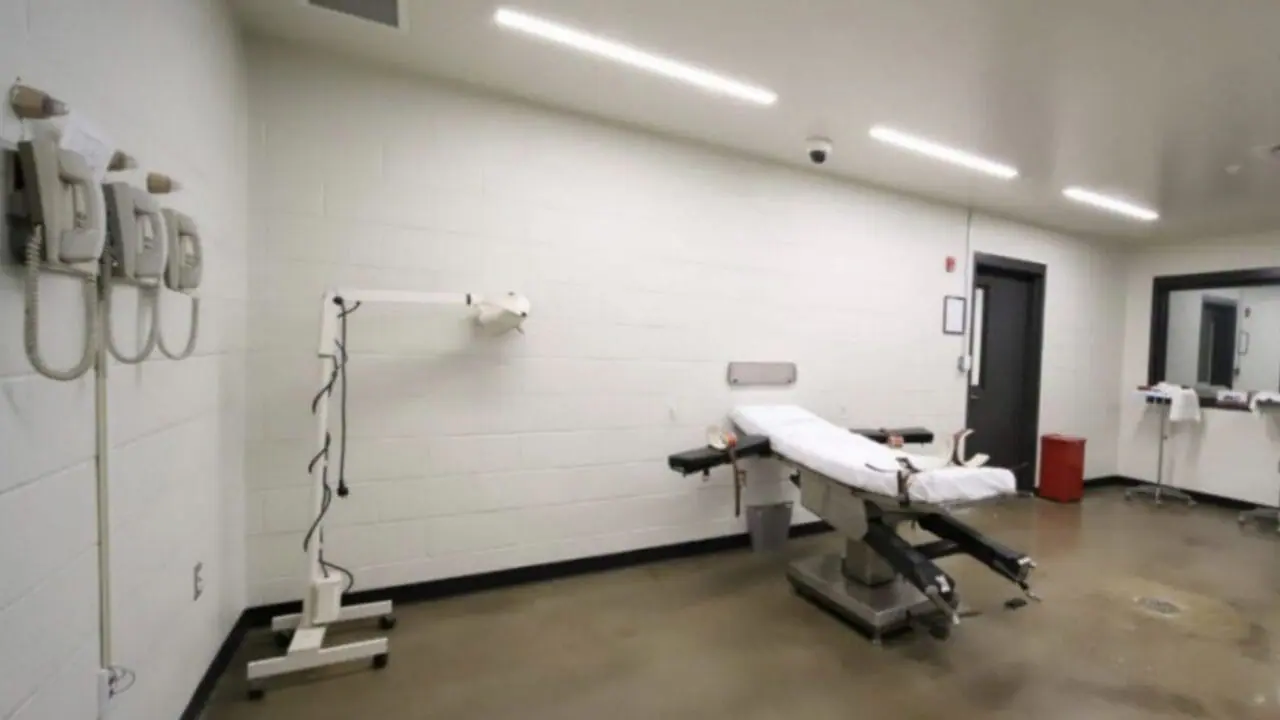

When a prisoner is executed, he or she is strapped to a gurney in a white cinder block room, containing one two-way window, and another window affixed with retractable blinds. Once given the OK by the prison warden, an IV line is inserted, and a lethal substance, or substances, is injected.

State law doesn’t specify what drugs are to be used for executions, saying only that the drugs must be injected intravenously in a quantity and for an amount of time sufficient to kill the inmate.

Previously, Indiana used a lethal combination of three substances to induce death. A new one-drug method, using pentobarbital, is expected for Corcoran’s execution.

Under Indiana law, only the following are allowed to be present during an execution:

- the state prison warden

- the assigned executioner, and any necessary assistants

- the prison physician, as well as one other physician

- the convicted person’s spiritual advisor

- the prison chaplain

- up to five friends or relatives invited by the inmate

- up to eight members of the victim’s immediate family who are at least 18 years old

Victims’ families were not explicitly permitted to witness executions until state legislators amended the law in 2006. Not long after the policy was enacted, family members of Juan Placencia — who was killed by David Leon Woods in 1984 in Garrett — told reporters that their ability to witness Woods’ death in May 2007 helped provide closure. They were the first family members to witness an execution under the law.

The lists of witnesses are often private, but past media reports show the most recent Indiana executions were attended by the victim’s family, attorneys, spiritual advisers and various prison staff.

Once pronounced dead, the inmate’s family can request for the body to be released to a funeral home, or the deceased can be cremated and buried at the cemetery at the Indiana State Prison.

A final grasp at clemency?

After Corcoran’s petition is filed, Komp said he expects clemency proceedings to commence soon after.

With clemency, the governor — in tandem with Indiana’s Parole Board — can elect to commute a death sentence to life imprisonment or grant a pardon for a criminal offense.

The Indiana Constitution gives the governor exclusive authority to grant reprieves, commutations, and pardons for all offenses — including capital crimes — except for treason and impeachment. The parole board is tasked by state law with assisting in that process.

The five-member board, specifically, is responsible for conducting an investigation into the merits of a clemency petition.

Shortly after an execution date is set, the board sets a schedule for the filing of clemency petition; submission of supporting materials; an interview and psychiatric examination of the death row inmate; a public hearing; and a public announcement of the parole board’s recommendation.

Members of the press and the general public are permitted to attend the inmate’s interview.

The subsequent public hearing — which Komp said will likely be scheduled “pretty quickly” — typically takes place two or three days prior to the execution date and is held in the Indiana Government Center in Indianapolis.

Each side — the state and counsel for the death row inmate — is given 90 minutes to present their case for or against clemency. The parole board presides over the hearing, and frequently interjects with questions.

Once complete, board members individually submit their recommendations to the governor, who has final say over the matter.

While not traditionally part of the clemency deliberations, Komp said his team are additionally seeking to “sit down” with Holcomb’s general counsel before a decision is made. He pointed to Missouri, Oklahoma, Kentucky and other jurisdictions that ensure such a meeting.

“We’re going to request to have that opportunity to answer any questions that the governor may have, that his general counsel may have,” Komp said. “What we’ve found in other jurisdictions is they have questions. Having an hour meeting and getting to say, ‘This is our pitch. Do you have any questions? Or is there something that the parole board said that you have a question or a concern about?’ Or maybe there’s something they think the parole board didn’t necessarily characterize correctly, because context matters, and we can provide context for something that we think is being misconstrued. So it’s not to get in the way — just provide accuracy.”

Three clemencies have been granted in Indiana since 1976, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

In 2004, former Indiana Gov. Joe Kernan commuted the death sentence of Darnell Williams to life imprisonment without parole on the basis that his co-defendant initially received a life sentence, making it “unjust” to execute only Williams.

Kernan, a Democrat, commuted another death sentence in 2005 of Michael Daniels, emphasizing doubts about Daniels’ personal responsibility for the crime and the quality of legal process leading to his death sentence.

The most recent was in 2009, when then-Gov. Mitch Daniels commuted the death sentence for Arthur Baird, who killed his pregnant wife and her parents in 1985. Although the Board of Paroles denied his petition for clemency, Daniels granted Baird clemency one day before the scheduled execution, in part citing questions about Baird’s sanity.

The former Republican governor additionally noted that life without parole in murder cases was not an option at the time of Baird’s sentencing; it became an option in 1994.

Other details still under wraps

A DOC spokesperson did not answer specific questions about who will be permitted to witness Corcoran’s execution. The department said only that a staging area for media will be available outside of the state prison, “and additional information will be provided closer to the date of the execution.”

The agency has also avoided answering questions about the drug acquired to resume executions in the state.

It wasn’t until June that Holcomb, along with Indiana’s attorney general, announced that the state’s Department of Correction has obtained pentobarbital to carry out the death penalty.

t remains unclear how the state obtained the pentobarbital. The governor’s office has declined to say where the drug was acquired, citing state law. Lawmakers made information about the source of the drugs confidential on the last day of the 2017 legislative session.

The Capital Chronicle filed a records request June 30 seeking the cost of the drugs. The Indiana Department of Correction has yet to fulfill the request.

Idaho reportedly spent $100,000 earlier this year to purchase three doses of pentobarbital, the drug used in lethal injections. It’s not clear if that’s the same quantity purchased or price paid by Indiana, however.

In 2015, a fiscal report prepared by Indiana General Assembly found that the average cost of a death penalty trial in the Hoosier State was $385,458 — nearly 10 times more than the cost of trial and appeal for cases in which the prosecution seeks a maximum sentence of life without parole.

Corcoran’s legal counsel have called on the state in recent court filings to make public protocols for the new execution drug’s use, including the amount of pentobarbital in Indiana’s possession, the drug’s expiration date and details about its potency and sterility.

Advocates additionally said it’s critical for the public to know who will be administering the drug — and how — as well as what training those individuals will receive.

Although no state-level executions in Indiana have used pentobarbital before, 13 federal executions carried out at the Federal Correctional Complex in Terre Haute have been carried out with the drug. Fourteen states have used pentobarbital in executions, too.

“All we want is what we are absolutely entitled to under Indiana law. And there’s no excuse why they have been unable to produce this since June. They have no explanation for why they’re dragging their heels on this,” Komp said. “Have the (attorney general) say they didn’t violate any federal or state laws in acquiring these drugs. That’s what we want. We gave the attorney general an opportunity in a legal filing to say they dotted their eyes and crossed their t’s, and they have refused to do so. Now here we are, two months after that, and we’ve still gotten crickets from them. So, we’re going to take all proper measures to pursue those rights and to make sure that everything’s on the up and up.”