On federal death row, inmates talk about Biden, executions

CHICAGO (AP) — On federal death row, prisoners fling notes on a string under each other’s cell doors and converse through interconnected air ducts. A top issue these days: whether President Joe Biden will halt executions, several told The Associated Press.

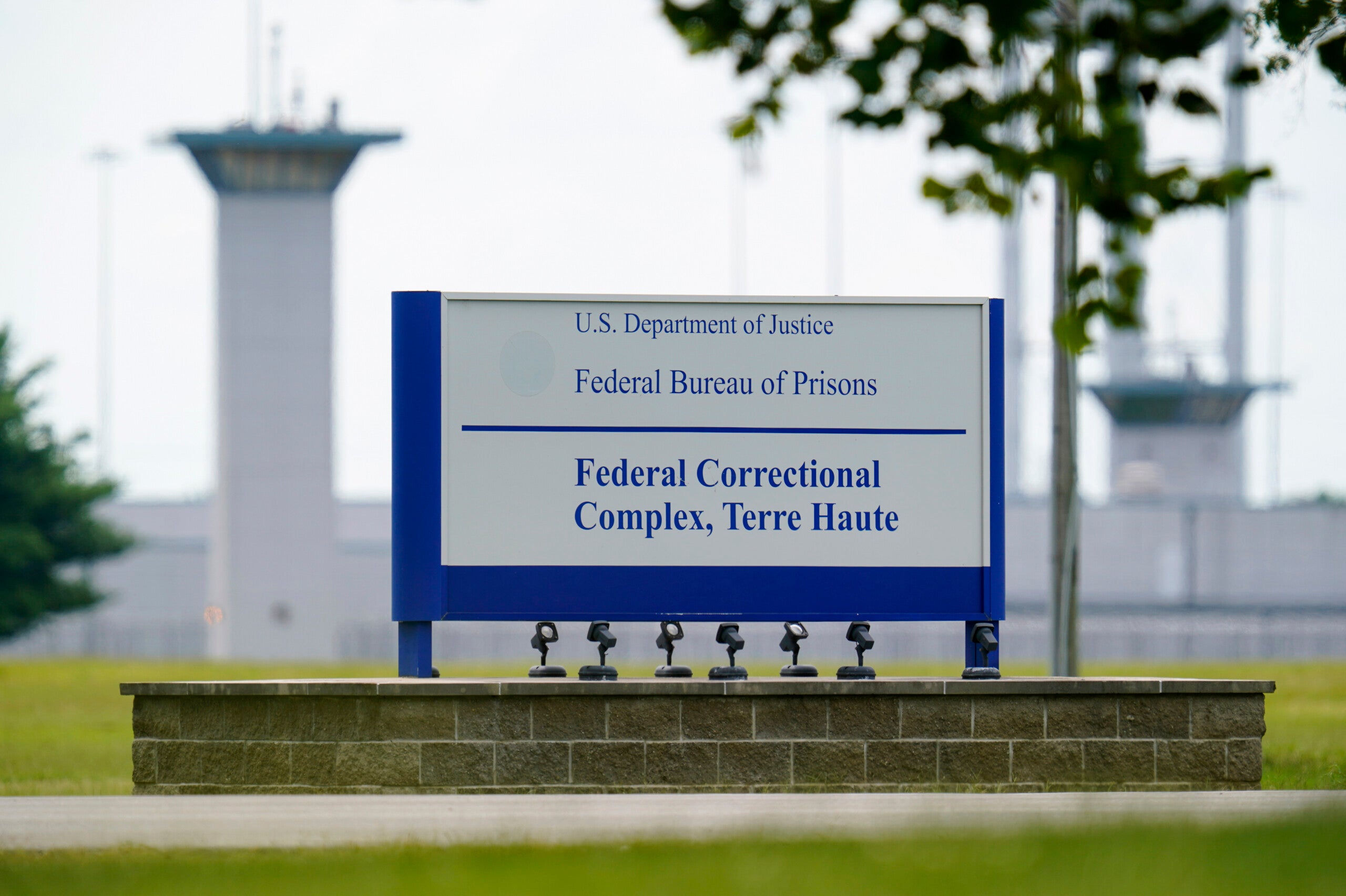

Biden hasn’t spoken publicly about capital punishment since taking office four days after the Trump administration executed the last of 13 inmates at the Terre Haute, Indiana, penitentiary where all federal death row inmates are held. The six-month run of executions cut their unit from around 63 to 50. Biden’s campaign website said he’d work to end federal executions, but he’s never specified how.

Four inmates exchanged emails with the AP through a prison-monitored system they access during the two hours a day they are let out of their 12-by-7-foot, single-inmate cells. Biden’s silence has them on edge, wondering whether political calculations will lead him to back off far-reaching action, like commuting their sentences to life in prison and endorsing legislation striking capital punishment from U.S. statutes.

“There’s not a day that goes by that we’re not scanning the news for hints of when or if the Biden administration will take meaningful action to implement his promises,” said 36-year-old Rejon Taylor, sentenced to death in 2008 for killing an Atlanta restaurant owner.

Everyone on federal death row was convicted of killing someone, their victims often suffering brutal, painful deaths. The dead included children, bank workers and prison guards. One inmate, white supremacist Dylann Roof, killed nine Black members of a South Carolina church during a Bible study in 2015. Many Americans believe death is the only salve for such crimes.

Views of capital punishment, though, are shifting. One recent report found people of color are overrepresented on death rows nationwide. Some 40% of federal death row inmates are Black, compared with about 13% of the U.S. population. With growing scrutiny of who gets sentenced to die and why, support for the death penalty has waned, and fewer executions are done overall. Virginia lawmakers recently voted to abolish it.

The death row prisoners expressed relief at Donald Trump’s departure from the White House after he presided over more federal executions than any other president in 130 years. Gone is the ever-present fear that guards would appear at their cell door to say the warden needed to speak to them — dreaded words that meant your execution had been scheduled.

They described death row as a close-knit community where bonds are forged. All said they were still reeling from seeing friends escorted away for execution by lethal injection at a garage-size building nearby.

“When it’s quiet here, which it often is, you’ll hear someone say, ‘Damn, I can’t believe they’re gone!’ We all know what they are referencing,” said Daniel Troya, sentenced in 2009 for participating in drug-related killings of a Florida man, his wife and their two children.

The federal executions during the coronavirus pandemic were likely superspreader events. In December, 70% of the death row inmates had COVID-19, some possibly infected via air ducts through which they communicate.

The AP attended all 13 federal executions.

Five of the first six inmates executed were white. Six of the last seven were Black, including Dustin Higgs, the final inmate put to death, on Jan. 16 for ordering the killing of three Maryland women.

Memories of speaking to Higgs just before his execution still pain Sherman Fields, who is on death row but has a resentencing for convictions in the killing of his girlfriend after escaping from a jail in Waco, Texas.

“He kept saying he’s innocent and he didn’t want to die,” Fields, 46, said. “He’s my friend. It was very hard.”

While there were rumors Biden would take action on the death penalty in his first days as president, there have been no announcements. As he grapples with issues like the coronavirus and the economy, capital punishment appears to be on a back burner. Meanwhile, federal prosecutors are still saying they’ll pursue death sentences.

Even if he’d hoped to, Biden can’t set aside the death penalty issue entirely. It came up Monday when the Supreme Court said it will consider a request — first made by the Trump administration — to reinstate the death sentence for Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev that a lower court tossed in July. The Biden administration could chose to say the government no longer opposes the lower court decision, though that, like everything with the death penalty, would undoubtedly create controversy.

The easiest step politically for Biden would be to simply instruct his Justice Department not to carry out any executions during his presidency. That would spare inmates’ lives for at least four years but would leave the door open for a future president to resume them.

The inmates first learned federal executions would restart after 17 years in 2019 when the first inmates were put on execution lists. More were added throughout 2020.

Through last year, inmates would flinch whenever they heard the jangle of thick key rings as a larger-than-normal contingent of guards entered their floor. That sound meant guards would soon stop at an inmate’s door and that he’d soon be in the warden’s office to be handed his death warrant.

When a frantic Keith Nelson, convicted of raping and killing a Kansas girl, kept saying a year ago he was sure he’d be selected next to die, one inmate yelled at him to “shut up,” that he was unnerving everyone else, Troya recalled. Nelson was executed on Aug. 28.

Emotions ran high as execution days approached. As guards led condemned men away, other inmates shouted, “Come on! Fight ’em!” Troya said. None appeared to resist.

Inmates can’t access the regular internet but could follow news of last-minute appeals on TVs in their cells. When broadcasts confirmed an execution had been carried out, Taylor said, a hush fell on death row, followed by a chorus of curses.

Inmates know that Biden, while a senator, played a key role in passing a 1994 crime bill that increased federal crimes for which someone could be put to death.

“I don’t trust Biden,” Troya said. “He set the rules to get us all here in the first place.”

Several inmates said Brandon Bernard’s death was especially hard to process. They described him as introspective and kind. Bernard, convicted of participating in the Texas carjacking, robbery and killing of an Iowa couple, also organized a death-row crocheting group that shared patterns and knitting tips.

“The gentlest guy on federal death row,” Fields said.

Bernard’s case drew the attention of reality TV star Kim Kardashian and other celebrities, who pleaded on Twitter for Trump to commute his sentence.

His lawyers said Bernard, 18 at the time and the lowest-ranking member of a street gang, was pressured to light a car on fire with Todd and Stacie Bagley’s bodies inside. They said he believed the Bagleys were already dead after a gang leader shot them in the head.

He and co-defendant Christopher Vialva, both of whom were Black, were convicted by a nearly all-white Texas jury in 2000.

Strapped to a cross-shaped gurney on Dec. 10, Bernard addressed the couple’s relatives in an adjoining death-chamber witness room, repeatedly apologizing and telling them he hoped his death would bring them closure.

After his execution, Todd Bagley’s mother called the killings an “act of unnecessary evil.” She said the executions of Bernard and of Vialva months earlier did bring closure. But she also expressed gratitude to both for apologizing. Beginning to cry, she told reporters: “I can very much say — I forgive them.”

Troya said he thinks often about Bernard, Vialva and Higgs, whom he considered close friends. All three, he said, had long since transformed themselves into better people and were mentoring other inmates.

“They killed future prison role models,” he said. “So much potential, lost for nothing.”