Female inmate’s execution on hold; 2 more halted over COVID at Terre Haute

TERRE HAUTE, Ind. (AP) — The U.S. government’s plans to carry out its first execution of a female inmate in nearly seven decades were on hold Tuesday amid a flurry of legal rulings, and two other executions set for later this week were halted because the inmates tested positive for COVID-19.

The three executions were to be the last before President-elect Joe Biden, an opponent of the federal death penalty, is sworn-in next week. Now it’s unclear how many additional executions there will be under President Donald Trump, who resumed federal executions in July after 17-year pause. Ten federal inmates have since been put to death.

Lisa Montgomery faced execution Tuesday for killing 23-year-old Bobbie Jo Stinnett in the northwest Missouri town of Skidmore in 2004. She used a rope to strangle Stinnett, who was eight months pregnant, and then cut the baby girl from the womb with a kitchen knife. Montgomery took the child with her and attempted to pass the girl off as her own.

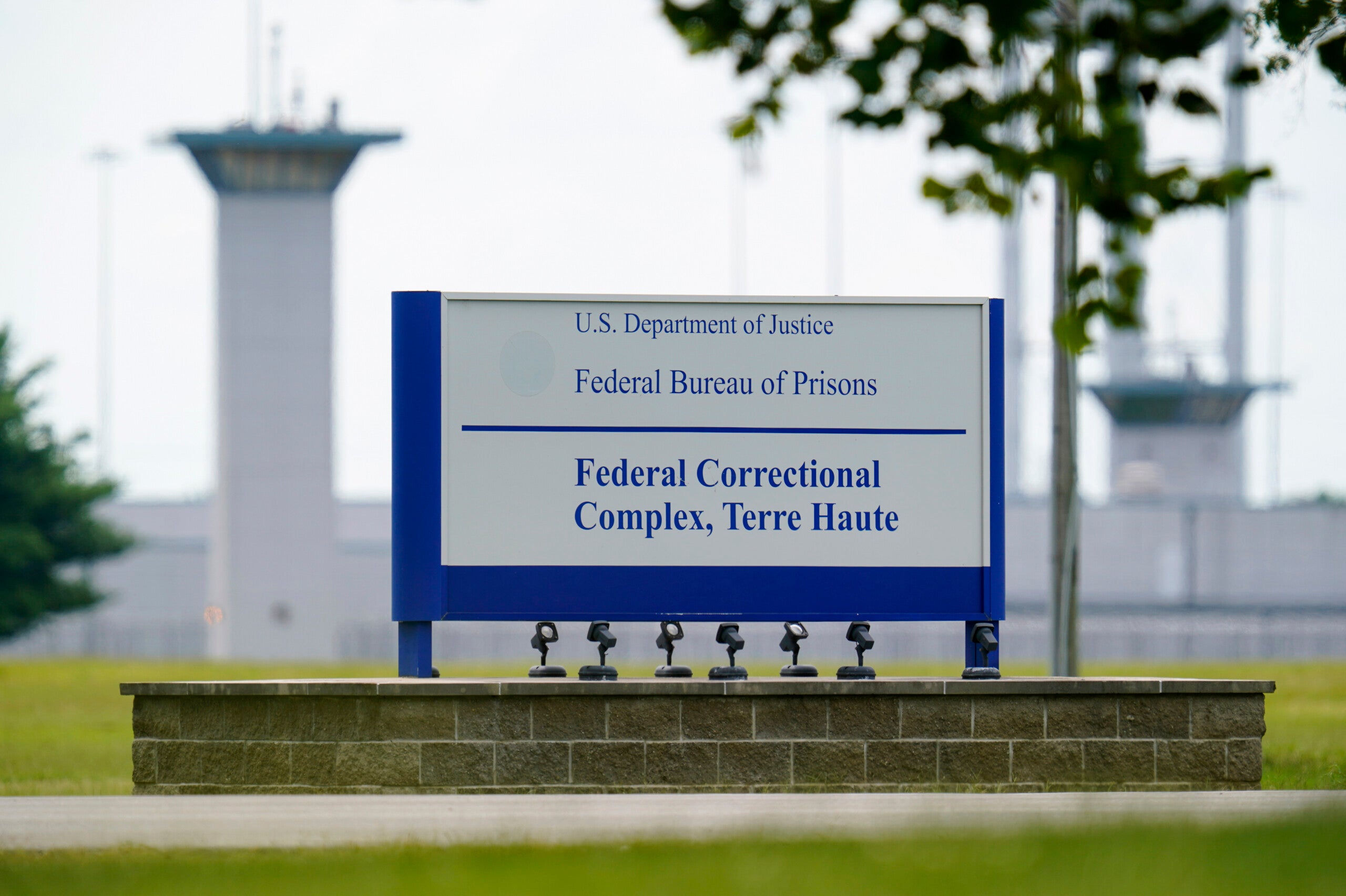

But an appeals court granted a stay of execution Tuesday, shortly after another appeals court lifted an Indiana judge’s ruling that found she was likely mentally ill and couldn’t comprehend she would be put to death. If a higher court puts the execution back on, Montgomery, the only female on federal death row, would receive a lethal injection at a federal prison complex in Terre Haute, Indiana. By Tuesday night, the Supreme Court lifted a separate injunction that was put in place by the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

Separately, a federal judge for the U.S. District of Columbia halted the scheduled executions later this week of Corey Johnson and Dustin Higgs in a ruling Tuesday. Johnson, convicted of killing seven people related to his drug trafficking in Virginia, and Higgs, convicted of ordering the murders of three women in Maryland, both tested positive for COVID-19 last month.

Delays of any of this week’s scheduled executions beyond Biden’s inauguration next Tuesday would likely mean they will not happen any time soon, or ever, since a Biden administration is expected to oppose carrying out federal death sentences.

One of Montgomery’s lawyers, Kelley Henry, told The Associated Press Tuesday morning that her client arrived at the Terre Haute facility late Monday night from a Texas prison and that, because there are no facilities for female inmates, she was being kept in a cell in the execution-chamber building itself.

“I don’t believe she has any rational comprehension of what’s going on at all,” Henry said.

Montgomery has done needle-point in prison, making gloves, hats and other knitted items as gifts for her lawyers and others, Henry said. She hasn’t been able to continue that hobby or read since her glasses were taken away from her out of concern she could kill herself.

“All of her coping mechanisms were taken away from her when they locked her down” in October when she was informed she had an execution date, Henry said.

Montgomery’s legal team says she suffered “sexual torture,” including gang rapes, as a child, permanently scarring her emotionally and exacerbating mental-health issues that ran in her family.

At trial, prosecutors accused Montgomery of faking mental illness, noting that her killing of Stinnett was premeditated and included meticulous planning, including online research on how to perform a C-section.

Henry balked at that idea, citing extensive testing and brain scans that supported the diagnosis of mental illness.

“You can’t fake brain scans that show the brain damage,” she said.

Henry said the issue at the core of the legal arguments are not whether she knew the killing was wrong in 2004 but whether she fully grasps why she is slated to be executed now.

In his ruling on a stay, U.S. District Judge James Patrick Hanlon in Terre Haute cited defense experts who alleged Montgomery suffered from depression, borderline personality disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Montgomery, the judge wrote, also suffered around the time of the killing from an extremely rare condition called pseudocyesis in which a woman’s false belief she is pregnant triggers hormonal and physical changes as if she was actually pregnant.

Montgomery also experiences delusions and hallucinations, believing God spoke with her through connect-the-dot puzzles, the judge said, citing defense experts.

“The record before the Court contains ample evidence that Ms. Montgomery’s current mental state is so divorced from reality that she cannot rationally understand the government’s rationale for her execution,” the judge said.

The government has acknowledged Montgomery’s mental issues but disputes that she can’t comprehend that she is scheduled for execution for killing another person because of them.

Details of the crime at times left jurors in tears during her trial.

Prosecutors told the jury Montgomery drove about 170 miles (274 kilometers) from her Melvern, Kansas, farmhouse to the northwest Missouri town of Skidmore under the guise of adopting a rat terrier puppy from Stinnett. She strangled Stinnett performing a crude cesarean and fleeing with the baby.

Prosecutors said Stinnett regained consciousness and tried to defend herself as Montgomery used a kitchen knife to cut the baby girl from her womb. Later that day, Montgomery called her husband to pick her up in the parking lot of a fast food restaurant in Topeka, Kansas, telling him she had delivered the baby earlier in the day at a nearby birthing center.

Montgomery was arrested the next day after showing off the premature infant, Victoria Jo, who is now 16 years old and hasn’t spoken publicly about the tragedy.

Prosecutors said the motive was that Montgomery’s ex-husband knew she had undergone a tubal ligation that made her sterile and planned to reveal she was lying about being pregnant in an effort to get custody of two of their four children. Needing a baby before a fast-approaching court date, Montgomery turned her focus on Stinnett, whom she had met at dog shows.

Anti-death penalty groups said Trump was pushing for executions prior to the November election in a cynical bid to burnish a reputation as a law-and-order leader.

The last woman executed by the federal government was Bonnie Brown Heady on Dec. 18, 1953, for the kidnapping and murder of a 6-year-old boy in Missouri.

The last woman executed by a state was Kelly Gissendaner, 47, on Sept. 30, 2015, in Georgia. She was convicted of murder in the 1997 slaying of her husband after she conspired with her lover, who stabbed Douglas Gissendaner to death.

Hollingsworth reported from Kansas.